In my last [post on Libya](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/09/libya-and-the-left/), I took a sort of squishy position: while avoiding a direct endorsement of the NATO military campaign there, I wanted to defend the existence of a genuine internal revolutionary dynamic, rather than dismissing the resistance to Gaddafi as merely the puppets of Western imperialism. I still basically stand by that position, and I still think the ultimate trajectory of Libya remains in doubt. But all that aside, it's important to look back carefully at the run-up to the military intervention. A couple of recent essays have tried to do so---one of them is an exemplary struggle to get at the real facts around the decision to go to war, while the other typifies the detestable self-congratulatory moralizing of the West's liberal warmongers.

The right way to look back on Libya is [this article](http://www.lrb.co.uk/v33/n22/hugh-roberts/who-said-gaddafi-had-to-go) in the *London Review of Books*, which I found by way of Corey Robin. Hugh Roberts, formerly of the International Crisis Group, casts a very skeptical eye on the claims made by the the NATO powers in the run-up to war, and on the intentions of those who were eager to intervene on the side of the Libyan rebels. At the same time, he acknowledges the intolerable nature of the Gaddafi regime and accepts the reality of an internally-generated political resistance that was not merely fabricated by external powers. But rather than accepting the claims of foreign powers at face value, he shows all the ways in which NATO actually managed to subvert the emergence of a real democratic political alternative in Libya, and he leaves me wondering once again whether the revolution would have been better off if it could have proceeded without external interference.

There are a few particularly important points that I want to draw out of Roberts' essay. First, he shows that, in a pattern that is familiar from the recent history of "humanitarian" interventions, many of the claims that were used to justify the imminent necessity of war do not hold up under scrutiny. First, there is the claim that military force had to be used because all other options had been exhausted. As Roberts observes:

> Resolution 1973 was passed in New York late in the evening of 17 March. The next day, Gaddafi, whose forces were camped on the southern edge of Benghazi, announced a ceasefire in conformity with Article 1 and proposed a political dialogue in line with Article 2. What the Security Council demanded and suggested, he provided in a matter of hours. His ceasefire was immediately rejected on behalf of the NTC by a senior rebel commander, Khalifa Haftar, and dismissed by Western governments. ‘We will judge him by his actions not his words,’ David Cameron declared, implying that __Gaddafi was expected to deliver a complete ceasefire by himself: that is, not only order his troops to cease fire but ensure this ceasefire was maintained indefinitely despite the fact that the NTC was refusing to reciprocate.__ Cameron’s comment also took no account of the fact that Article 1 of Resolution 1973 did not of course place the burden of a ceasefire exclusively on Gaddafi. No sooner had Cameron covered for the NTC’s unmistakable violation of Resolution 1973 than Obama weighed in, insisting that for Gaddafi’s ceasefire to count for anything he would (in addition to sustaining it indefinitely, single-handed, irrespective of the NTC) have to withdraw his forces not only from Benghazi but also from Misrata and from the most important towns his troops had retaken from the rebellion, Ajdabiya in the east and Zawiya in the west – in other words, he had to accept strategic defeat in advance. These conditions, which were impossible for Gaddafi to accept, were absent from Article 1.

Whether or not you believe that the Gaddafi side would ever have seriously engaged in negotiations over a peaceful settlement, or whether you think such negotiations would have been preferable to complete rebel military victory, it seems clear that the NATO powers never really gave them the chance. This is reminiscent of what happened prior to the bombing of Serbia in 1999: NATO started bombing after claiming that Serbia refused a peaceful settlement of the Kosovo conflict. What actually happened was that NATO presented the Serbs with a "settlement" that would have [given NATO troops](http://www.inthesetimes.com/projectcensored/ackerman2317new.html) the right to essentially take control of Serbia. The Serbs understandably objected to this, though they were willing to accept international peacekeepers. But this wasn't enough for NATO, and so it was bombs away.

A second element of the brief for the Libya war that Roberts highlights is the peculiar case of the imminent Benghazi massacre. Recall that among the war's proponents, it was taken as accepted fact that, when NATO intervened, Gaddafi's forces were on the verge of conducting a genocidal massacre of civilians in rebel-held Benghazi, and thereby snuffing out any hope for the revolution. Here is what Roberts has to say about that:

> Gaddafi dealt with many revolts over the years. He invariably quashed them by force and usually executed the ringleaders. The NTC and other rebel leaders had good reason to fear that once Benghazi had fallen to government troops they would be rounded up and made to pay the price. So it was natural that they should try to convince the ‘international community’ that it was not only their lives that were at stake, but those of thousands of ordinary civilians. But in retaking the towns that the uprising had briefly wrested from the government’s control, Gaddafi’s forces had committed no massacres at all; the fighting had been bitter and bloody, but there had been nothing remotely resembling the slaughter at Srebrenica, let alone in Rwanda. The only known massacre carried out during Gaddafi’s rule was the killing of some 1200 Islamist prisoners at Abu Salim prison in 1996. This was a very dark affair, and whether or not Gaddafi ordered it, it is fair to hold him responsible for it. It was therefore reasonable to be concerned about what the regime might do and how its forces would behave in Benghazi once they had retaken it, and to deter Gaddafi from ordering or allowing any excesses. But that is not what was decided. What was decided was to declare Gaddafi guilty in advance of a massacre of defenceless civilians and instigate the process of destroying his regime and him (and his family) by way of punishment of a crime he was yet to commit, and actually unlikely to commit, and to persist with this process despite his repeated offers to suspend military action.

Roberts goes on to cast doubt on one of the specific claims of atrocity against Gaddafi: that his air force was strafing protestors on the ground. This claim was widely propagated by media like Al-Jazeera and liberal war-cheerleaders like Juan Cole, but Roberts finds no convincing evidence that it ever actually occurred. Reporters who were in Libya didn't get reports of it, nor is there any photographic evidence---this despite the ubiquity of cell-phone camera footage in the wave of recent uprisings. The evaporation of the sensational allegation calls to mind the run-up to yet another war: the first Gulf War, when the invasion of Iraq was sold, in part, by way of a [thoroughly made up](http://www.csmonitor.com/2002/0906/p25s02-cogn.html) story about Iraqi troops ripping Kuwaiti babies out of incubators and leaving them to die.

Beyond revealing the weakness of the empirical case for war, Roberts also highlights something I hadn't really thought of before: the way the West's case for intervention promotes an anti-political and undemocratic framing of the conflict that has a lot in common with the sort of anti-ideological elite "non-partisanship" that I [wrote about](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/10/polarization-and-ideology/) a couple of weeks ago in the context of domestic politics. Roberts observes that the NATO powers portrayed themselves as the defenders of an undifferentiated "Libyan people" rather than partisans taking one side in a civil war. By doing so, they short-circuited the development of a real political division within Libyan society, a development that in itself was a desirable process:

> __The idea that Gaddafi represented nothing in Libyan society, that he was taking on his entire people and his people were all against him was another distortion of the facts.__ As we now know from the length of the war, the huge pro-Gaddafi demonstration in Tripoli on 1 July, the fierce resistance Gaddafi’s forces put up, the month it took the rebels to get anywhere at all at Bani Walid and the further month at Sirte, Gaddafi’s regime enjoyed a substantial measure of support, as the NTC did. __Libyan society was divided and political division was in itself a hopeful development since it signified the end of the old political unanimity enjoined and maintained by the Jamahiriyya.__ In this light, the Western governments’ portrayal of ‘the Libyan people’ as uniformly ranged against Gaddafi had a sinister implication, precisely because it insinuated a new Western-sponsored unanimity back into Libyan life. This profoundly undemocratic idea followed naturally from the equally undemocratic idea that, in the absence of electoral consultation or even an opinion poll to ascertain the Libyans’ actual views, the British, French and American governments had the right and authority to determine who was part of the Libyan people and who wasn’t. No one supporting the Gaddafi regime counted. Because they were not part of ‘the Libyan people’ they could not be among the civilians to be protected, even if they were civilians as a matter of mere fact. And they were not protected; they were killed by Nato air strikes as well as by uncontrolled rebel units. The number of such civilian victims on the wrong side of the war must be many times the total death toll as of 21 February. But they don’t count, any more than the thousands of young men in Gaddafi’s army who innocently imagined that they too were part of ‘the Libyan people’ and were only doing their duty to the state counted when they were incinerated by Nato’s planes or extra-judicially executed en masse after capture, as in Sirte.

It's possible, after reading all of Roberts' essay, to remain convinced that the NATO attack was a lesser evil on balance, and to retain some optimism about the future trajectory of Libya. But he nevertheless provides an important reminder of just why it's so important to beware of Presidents bearing "humanitarian" interventions. The liberal war-mongering crowd likes to deride those of us who bring strongly anti-interventionist biases into these debates, on the grounds that we are irrationally prejudiced against the United States, or against the possible benefits of war. But in the immediate prelude to war, such biases are in fact entirely rational, precisely because the real dynamics on the ground are so murky and hard to determine, and the arguments used to justify intervention so often turn out to be illusory after the fact.

This reality does not, however, prevent the liberal hawk faction from coming out with some triumphant breast-beating and score-settling when their little war looks to be a "success". Michael Berube has a [new essay](http://www.thepointmag.com/2011/politics/libya-and-the-left) in this genre, and it's terrible in all the ways the Roberts essay is excellent. In both tone and content, it's a shameful piece of writing, and Berube should be embarrassed to have written it---but since it placates the tortured soul of the liberal bombardier, he is instead [hailed](http://www.juancole.com/2011/11/berube-on-libya-and-the-left.html) as a brave and sophisticated thinker.

Berube argues that opponents of the war in Libya are fatally flawed by a "manichean" approach to foreign policy: rather than appreciate the nuances of the situation in Libya, he claims, opponents of the war lazily fell back on "tropes that have been forged over the past four decades of antiwar activism". These tropes, says Berube, are an impediment to forging "a rigorously *internationalist* left in the U.S., a left that will promote and support the freedom of speech, the freedom to worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear—even on those rare and valuable occasions when doing so puts one in the position of supporting U.S. policies."

This is, I suppose, an improvement on Michael Walzer's call for a "decent" left (where "decency" consists of an appropriate deference to U.S. imperial propaganda). But as the Roberts essay shows, the pro-war faction are on shaky ground when they accuse others of relying on a ritualized set of tropes: the imminent humanitarian disaster and the impossibility of a non-military solution are themselves the repetitive--and routinely discredited--way in which war is sold to those who consider themselves liberals and internationalists. The eagerness of people like Berube to pick up on any thinly-sourced claim that vindicates the imminence and necessity of bombs suggests that the case for humanitarian intervention has become increasingly routinized as the Libyas, Iraqs, and Serbias pile up.

And it is striking that, in contrast to the careful skepticism of Roberts, Berube simply assumes that NATO action was necessary to prevent imminent catastrophe. In doing so, he evades all the difficult questions that arise in the Roberts essay. He relies, for example, on Juan Cole's refutation of numerous alleged "myths" of the anti-interventionists; among them is the argument that "Qaddafi would not have killed or imprisoned large numbers of dissidents in Benghazi, Derna, al-Bayda and Tobruk if he had been allowed to pursue his March Blitzkrieg toward the eastern cities that had defied him". Berube derides this claim as "bizarre", and indeed it would be if this were actually the argument that any serious party had made. But the argument for intervention was not merely that Gaddafi could potentially have "killed or imprisoned large numbers of dissidents". As Roberts notes, that's the inevitable end result of just about any failed armed rebellion, and imprisonment and killing was probably an unavoidable endgame no matter how matters in Libya were resolved. The victorious rebels, after all, have imprisoned or extrajudicially killed a large number of people on the pro-Gaddafi side, including Gaddafi himself; and that's not to speak of the direct civilian casualties from the actual bombing campaign.

But Berube elides all of this, by implying that those who questioned the predictions of a humanitarian apocalypse were absurdly denying the possibility of *any retaliation at all* against the rebels. Thus, while acknowledging that in principle "the Libya intervention could be subjected to cost/benefit analyses and consequentialist objections", he proceeds to pile up the human costs of non-intervention, while leaving his side of the ledger clear of any of the deaths that resulted from the decision to intervene. This allows him to portray the pro-intervention side as the sole owners of facts and common sense, before launching into his real subject: the perfidy and moral obtuseness of the war's critics.

He finds plenty of juicy targets, because there was indeed some dodgy argumentation on the anti-war side. There was, as there always is, a certain amount of vulgar anti-imperialism that insisted that opposing NATO meant glorifying Gaddafi and dismissing the legitimacy of his opposition. There was, too, an occasional tendency to obsess over the war's legality, even though law in an international context is always rather capricious and dependent on great-power politics. And Berube is clever enough to anticipate the objections to his highlighting of such arguments:

> Those who believe that there should be no enemies to one’s left are fond of accusing me of “hippie punching,” as if, like Presidents Obama and Clinton, I am attacking straw men to my left in order to lay claim to the reasonable, vital center; those who know that I am not attacking straw persons are wont to claim instead that I am criticizing fringe figures who have no impact whatsoever on public debate in the United States. And it is true: on the subject of Libya the usual fringe figures behaved precisely as The Left At War depicts the Manichean Left. Alexander Cockburn, James Petras, Robert Fisk, John Pilger—all of them still fighting Vietnam, stranded for decades on a remote ideological island with no way of contacting any contemporary geopolitical reality whatsoever—weighed in with the usual denunciations of US imperialism and predictions that Libya would be carved up for its oil. And about the doughty *soi-disant* anti-imperialists who, in the mode of Hugo Chavez, doubled down on the delusion that Qaddafi is a legitimate and benevolent ruler harassed by the forces of imperialism, there really is nothing to say, for there can be nothing more damning than their own words.

For the record: yes indeed, Berube *is* engaged in "hippie punching", attacking straw men, and selectively [nutpicking](http://www.slate.com/blogs/weigel/2011/10/21/the_limits_of_nutpicking.html) the worst arguments on the anti-war side. And to what end? As with so much liberal imperialism, it seems that the purpose here is not so much to provide an empirical and political case for the war, as it is to confirm the superior moral sensibility of the warmongers, who are committed to high-minded internationalist ideals while their opponents are mired in knee-jerk anti-Americanism. The conflation of good intentions with good results bedevils liberal politics in all kinds of ways, and nowhere is it more damaging than in the realm of international politics, where morally pure allegiances are difficult to find.

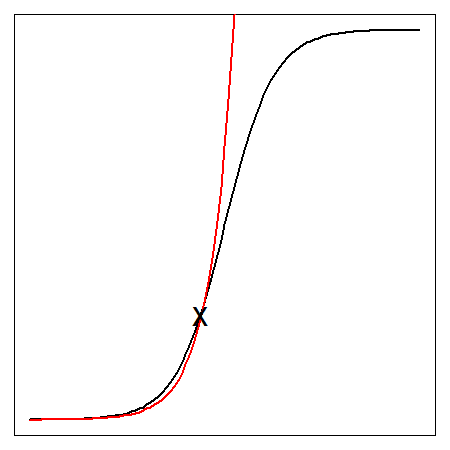

Berube complains that "for what I call the Manichean Left, opposition to U.S. policy is precisely an opposition to entities: all we need to know, on that left, is that the U.S. is involved." To this, he counterposes his rigorous case-by-case evaluation of specific actions, which is indifferent to the identity of the parties involved. But while this is a sound principle in the abstract, Roberts' exposé of the shaky Libya dossier demonstrates why it is so dangerous in practice. Given our limited ability to evaluate, in the moment, the hyperbolic claims made by governments on the warpath, a systematic bias against supporting intervention is the only way to counter-balance what would otherwise be a bias in favor of accepting propaganda at face value, and thereby supporting war in every case. Even if the outcome in Libya turns out to be an exceptional best-case scenario---a real democracy, independent of foreign manipulation---this is insufficient reason to substantially revise a general-purpose anti-interventionist [prior](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prior_probability). And even if the outcome of the NATO campaign has not played out as badly as some anti-war voices predicted, the details of that campaign's marketing only tend to confirm the danger of making confident statements of martial righteousness while enveloped in the fog of war.