Happy Agricultural Reform Day! link roundup

September 30th, 2011 | Published in Uncategorized

No, really: on this day São Tomé and Príncipe celebrates [the nationalization of large plantations](http://books.google.com/books?id=e59TqbPNAB0C&pg=PA80&lpg=PA80&dq=%22agricultural+reform+day%22&source=bl&ots=JAumaKUG9H&sig=aoynX5iyiSi0rFbpnARQWMaaK6U&hl=en&ei=ihWFToHBA8P40gHk0q0J&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAzgU#v=onepage&q=%22agricultural%20reform%20day%22&f=false). There should really be more holidays like that.

31 years ago today the [Ethernet specification](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethernet) was published, and without it this blog wouldn't be possible.

8 years ago today, [Yusuf Bey](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yusuf_Bey) died. I'm mentioning that mostly as an excuse to link to the insane saga of [Your Black Muslim Bakery](http://www.rickross.com/groups/bakery.html).

I've now risen high enough in Google's algorithms to get some interesting search engine traffic. My favorites from the past week or so:

- "how to short germany". Sorry, we're not a financial advice blog here, can't help you.

- "i'm reading huckleberry finn for english but i'm not getting what's going on at all". My one post on Huck Finn probably didn't help this guy either.

- "коммодификация". Google Translate tells me this is Russian for "commodification".

- "how does someone steal shoes from department stores". I believe stuffing them under your coat is a popular method.

- "do we still have capitalism". Good question! I think I actually do have some helpful things to say about this.

- "the book of job translation in modern english". I think this person was actually looking for information about "the job of book translation", which I do have one post about. But "the book of job translation" isn't a bad description of a lot of the other writing here.

- "business cycle turkey". [Mmmm](http://www.snpp.com/guides/mmmm.html), turkey.

Anyway, your links:

- What's that expression, it's not the crime, it's the pepper spraying? The media was all set to ignore the Wall Street protests, until the cops decided to [go buck wild](http://thelastword.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2011/09/26/7978720-rewrite-police-vs-protesters). Click that link to see former Daniel Patrick Moynihan advisor Lawrence O'Donnell sounding like vintage [Ice Cube](http://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/13/arts/pop-view-rap-after-the-riot-smoldering-rage-and-no-apologies.html): "There's a Rodney King every day in this country, and black America has always known that."

- Speaking of Ice Cube, ["My Summer Vacation"](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMqfRey10gA) is a great track about some LA gangbangers moving to Saint Louis to start up a new franchise. Listen to that as you read about [how today's gangs spread to America's smaller cities](http://botc.tcf.org/2011/09/mcbloods-gang-migration-and-the-franchising-of-american-street-gangs.html).

- And speaking of Occupy Wall Street, check out my pal Chris Maisano and my organization, the Democratic Socialists of America, in this [Salon article](http://www.salon.com/news/wall_street/index.html?story=/politics/war_room/2011/09/29/at_occupy_wall_street).

- More OWS: I haven't written anything about Occupy Wall Street because I'm not sure what to say about it, even though I'm rooting for it to succeed and expand. Perhaps because it's not sure [what to say about itself](http://lbo-news.com/2011/09/29/the-occupy-wall-street-non-agenda/). Still, it's looking like things are starting to [gather some momentum](http://www.dailykos.com/story/2011/09/29/1021378/-Occupy-Wall-Street-growing-rapidly).

- Just to be clear, the Obama administration is now in the business of [assassinating American citizens](http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/09/anwar-al-awlaki/245942/) whenever they feel like it, with no due process or legal oversight. In a different context, we'd use words like "death squad" to refer to stuff like this.

- Groupon seems like it's either an egregious scam or the next big tech company or possibly both, or perhaps just pure [bezzle](http://crookedtimber.org/2011/09/24/banks-and-the-bezzle/). Felix salmon [explains](http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/09/26/notes-on-groupon/) why the company may not be doomed, and why the huge amount of money taken out of the money-losing company by its founders could be a rational venture capitalist strategy rather than the crass looting I always figured it was. I still think they're doomed, though.

- I already mentioned it, but here again: [this series of articles](http://www.slate.com/id/2304442/) about the replacement of human labor with robots is quite good on the specifics of automation, but it goes with what's basically a "jobless future" argument, and is therefore probably wrong: capitalism is endlessly capable of coming up with things that humans can be paid to do. It's always a mistake to say "in the future there *will* be no jobs" rather than "in the future we *could* spent a lot less time in paid labor". The real lesson here is that there's no reason to keep coming up with alienating jobs for people, and we have the *opportunity* to live lives that are mostly free of the drudgery of unwanted work, but only if a political movement arises to make that happen. As always, see ["Anti-Star Trek"](http://www.peterfrase.com/2010/12/anti-star-trek-a-theory-of-posterity/), along with ["Against Jobs"](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/07/stop-digging-the-case-against-jobs/) and its [follow-up](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/07/against-jobs-for-full-employment/), for my more considered reflections on this topic.

- Oceania has always been at war against [inflation](http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=10991).

- Tom Slee [asked very nicely](http://whimsley.typepad.com/whimsley/2011/09/my-favourite-post.html) that everyone go read [this old post](http://whimsley.typepad.com/whimsley/2009/11/pirates-dilemma-review-remixed.html). Tom Slee is great, so you should do what he says.

- "That's probably the pragmatic way to look at it. But it seems to me, though, that it's a concession to a step back in civilization". You'll just have to [watch the whole thing](http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=lpRQrClgYsM#!) to find out what the context of that statement is. Salim Muwakkil is kind of a national treasure, but you probably don't know about him unless you've lived in Chicago. Should you happen to catch the fever, though, go on to watch [this clip](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cs281awSYF0), especially after about the six minute mark. "Did that kind of radicalize you, when you were shot?"

- If you like quantitative data, survey research, and corrections for measurement error, you'll __love__ [this video](http://youtu.be/3rZDEddKymU) about how the Census Bureau fixed an error in their new count of same-gender couples. Which is to say, I loved it. And if that doesn't have enough complicated mathematical equations for you, there's a [technical paper](http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/files/ss-report.doc)!

- New home sales in 2011 are on pace to be the [lowest since at least 1963](http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2011/09/on-pace-for-record-low-new-home-sales.html). Sales this year are at *less than a quarter* of what they were in 2005, at the peak of the bubble.

- Epic Bureau of Economic Analysis [fail](http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/09/27/how-macroeconomic-statistics-failed-the-us/). I knew that their initial estimates of the severity of the recession were off, but I hadn't caught that they revised the GDP growth number from Q4 2008 from -3.8% all the way down to *-8.9%*!!! Let this be a lesson to all us quants who rely on U.S. government statistics.

- Some random day trader got on TV and caused a big uproar by confirming every suspicion you ever had that finance guys are [amoral, callous assholes](http://youtu.be/lqN3amj6AcE) who don't actually care about the health of the global economy. Then people started to wonder whether the whole thing [might](http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/09/27/is-alessio-rastani-a-yes-man/) be [a Yes Men](http://www.thejournal.ie/is-alessio-rastani-actually-one-of-the-yes-men-237950-Sep2011/) [hoax](http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2011/09_september/27/statement.shtml).

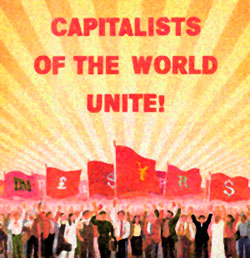

- Via the [Jacobin](http://www.jacobinmag.com) crew, I found out that it's [Capitalism Awareness Week](http://capitalismweek.org/). I hope that this consciousness-raising effort serves to increase awareness of the capitalism epidemic and the risk it poses to the public.

- ["If you're quick with a knife, you'll find that the invisible hand is made of delicious invisible meat"](http://xkcd.com/958/).

- I still don't know what the current Palestinian statehood initiative is actually going to amount to, but at least it's leading to things [like this](http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/tony-blair/8795251/Tony-Blairs-job-in-jeopardy-as-Palestinians-accuse-him-of-bias.html). Tony Blair is truly one of the most contemptible living humans.

- Anyone who took that [Onion story about congressional hostage-taking](http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/blogpost/post/the-onion-tweets-screams-and-gunfire--wheres-the-humor/2011/09/29/gIQASpCI7K_blog.html?tid=sm_twitter_washingtonpost) seriously, or thinks the Onion "went too far", is, to quote Charles Barkley, a stone freaking idiot.

- Corporations have figured out that they can [manipulate Tea Partiers](http://prospect.org/csnc/blogs/tapped_archive?month=09&year=2011&base_name=beyond_astroturf) into doing their lobbying for them.

- [Regime change doesn't work.](http://www.bostonreview.net/BR36.5/ndf_alexander_b_downes_regime_change_doesnt_work.php)