On the Politics of Basic Income

July 16th, 2018 | Published in Everyday life, Feminism, Political Economy, Politics, Socialism, Time, Work

In the course of preparing some brief comments on the [Universal Basic Income](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_income) for another site, I decided to write up my attempt to clarify some of the politics behind the current debates about UBI as a demand and as a policy. This is adapted from remarks I gave [earlier this year](https://business.leeds.ac.uk/about-us/article/universal-basic-income-and-the-future-of-work/) at the University of Leeds, for a symposium on the topic.

One of the major obstacles to clear discussion of UBI is the tendency to pose the issue as a simple dichotomy: one is either for or against basic income. In fact, however, it must be recognized that both the advocates and opponents of UBI contain right and left flanks. The political orientation one takes toward basic income--and in particular, whether one is considering it primarily from the perspective of labor, or of capital--has profound implications both for how one thinks a UBI should be fought for and implemented, and what one thinks it is meant to achieve.

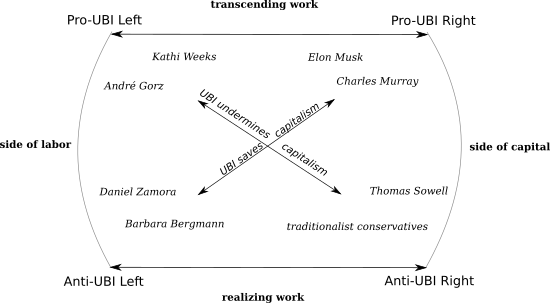

The multiple poles of the UBI debate are represented in the following diagram:

The Left-wing version of Basic Income is associated with thinkers like Kathi Weeks and André Gorz. Their hope is that with a basic income, as Weeks [puts it](http://criticallegalthinking.com/2016/08/22/feminist-case-basic-income-interview-kathi-weeks/), "the link between work and income would be loosened, allowing more room for different ways of engaging in work." Moreover, Weeks argues, drawing on the legacy of the Wages for Housework movement:

> Demanding a basic income, as I see it, is also a process of making the problems with the wage system of income allocation visible, articulating a critical vocabulary that can help us to understand these problems, opening up a path that might eventually lead us to demand even more changes, and challenging us to imagine a world wherein we had more choices about waged work, nonwork, and their relationship to the rest of our lives.

Left UBI advocates like Weeks tend to see basic income as part of a broader set of demands and proposals, rather than a single-shot solution to every social problem (though this monomaniacal focus does have its adherents on the Left.) They thus support what Los Angeles collective The Undercommons [refers to](https://bostonreview.net/class-inequality-race/undercommons-no-racial-justice-without-basic-income) as "UBI+," in which a baseline guaranteed income supplements other forms of support, which they contrast with "UBI-," "a basic income advanced as a replacement for labor regulations and other security-enhancing government programs."

The danger of Right-wing basic income, or UBI-, was identified by Gorz in his 1989 [*Critique of Economic Reason*](https://www.versobooks.com/books/509-critique-of-economic-reason):

> The guaranteed minimum is an income granted by the state, financed by direct taxation. It starts out from the idea that there are people who work and earn a good living and others who do not work because there is no room for them on the job market or because they are (considered) incapable of working. Between these two groups, no lived relation of solidarity emerges. This absence of solidarity (this society deficit) is corrected by a fiscal transfer. The state takes from the one group and gives to the other. . .

> . . . The guaranteed minimum or universal grant thus form part of a palliative policy which promises to protect individuals from the decomposition of wage-based society without developing a social dynamic that would open up emancipatory perspectives for them for the future.

Something like this vision animates much of the advocacy for UBI in capitalist and conservative circles. The clearest exposition of this perspective comes from far-right writer Charles Murray, co-author of the [infamous](http://books.wwnorton.com/books/The-Mismeasure-of-Man/) *The Bell Curve*. His 2006 book [*In Our Hands*](https://www.aei.org/publication/a-guaranteed-income-for-every-american/) roots his basic income proposal in the right-wing tradition of Milton Friedman, and its subtitle makes explicit what UBI is supposed to be: "A Plan to Replace the Welfare State." He insists on "getting rid of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, Supplemental Security Income, housing subsidies, welfare for single women and every other kind of welfare and social-services program, as well as agricultural subsidies and corporate welfare."

It is something like this version of UBI that appeals to the likes of [Elon Musk](https://www.fastcompany.com/4030576/elon-musk-says-automation-will-make-a-universal-basic-income-necessary-soon). It is also the prospect that drives some on the left to vociferously oppose the idea. Sociologist Daniel Zamora, who I've [sparred](https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/12/beyond-the-welfare-state/) [with](https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/06/social-democracy-polanyi-great-transformation-welfare-state) on occasion, [argues](https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/12/universal-basic-income-inequality-work) that "UBI isn’t an alternative to neoliberalism, but an ideological capitulation to it." He argues that a political and economically feasible basic income could only be something like Murray's proposal: too little to live on (thus promoting the spread of precarious low wage jobs) and paid for with drastic cuts to the rest of the welfare state. Moreover, he argues that even a relatively generous UBI would only intensify the logic of neoliberal capitalism, by perpetuating a condition in which makes "market exchange the nearly exclusive means to acquire the goods necessary for our own reproduction."

Zamora calls instead for reducing the scope of the market through the struggle for [decommodification](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/06/de-commodification-in-everyday-life/). This perspective is reflected by those like [Barbara Bergmann](https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/reducing-inequality-merit-goods-vs-income-grants), who [emphasize](http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0032329203261101?journalCode=pasa) the importance of directly providing "merit goods" like health care, education, and housing, rather than relying on the private market. This is important, because a Murray-style UBI- of marketized social provision would be radically inegalitarian for reasons I've [explained](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/04/health-care-and-the-communism-of-the-welfare-state/) elsewhere. Bergmann's prioritization of this substantive service provision is reflected in the advocates of ["Universal Basic Services"](https://universalbasicservices.org/) as an alternative to Universal Basic Income.

Of course, Charles Murray and Elon Musk are still somewhat anomalous within the broader pro-capitalist Right. Some, like [James Pethokoukis](https://www.aei.org/publication/universal-basic-income-uncertain-need-with-worrisome-potential-costs/), argue that UBI is an unnecessary expense, because the breathless predictions of mass technological employment are unlikely to come true (echoing some of the analysis of leftist critics like [Doug Henwood](https://lbo-news.com/2015/07/17/workers-no-longer-needed/)). Others, like [Thomas Sowell](https://www.creators.com/read/thomas-sowell/06/16/is-personal-responsibility-obsolete), are philosophically opposed to "divorcing personal rewards from personal contributions."

Having set up four different poles of attraction, it's worth thinking about what attracts and repels each position in the debate to each of the others, again with reference to the diagram above. What unites the pro-UBI forces is a willingness to think beyond a society defined by work as wage labor. Even Murray, more of a traditionalist than some of the Silicon Valley futurist types, argues that reduced labor force participation is an acceptable and even desirable consequence of UBI, because it would mean "new resources and new energy into an American civic culture," and "the restoration, on an unprecedented scale, of a great American tradition of voluntary efforts to meet human needs." This finds its left echoes in those like Gorz and Kathi Weeks, whose UBI advocacy stems from her [post-work](https://www.jacobinmag.com/2012/04/the-politics-of-getting-a-life/) politics.

Arrayed against the post-work vision of Basic Income are those who treat work as something to be realized and celebrated, rather than transcended or dispensed with. On the Left, this takes the form of various "dignity of labor" arguments which, to use Weeks' framing of the issue, insist that our main goal should be ensuring *better* work, not less work. Often this is tied to a defense of the inherent importance of meaningful work, as when the [head of the German Federation of Trade Unions](https://www.dw.com/en/german-trade-unions-strictly-against-basic-income-concept/a-43589741) argued recently that "pursuing a job was crucial to structure people's everyday lives and ensure social cohesion."

In his new book [*Radical Technologies*](https://www.versobooks.com/books/2742-radical-technologies), Adam Greenfield concludes his chapter on automation with a defense of jobs, which "offered us a context in which we might organize our skills and talents," or at least "filled the hours of our days on Earth." A recurrent reference point for the job-defenders, like [Ha-Joon Chang](https://newhumanist.org.uk/articles/5329/why-sci-fi-and-economics-have-more-in-common-than-you-think), is Kurt Vonnegut's 1952 novel *Player Piano*, which imagines a highly automated future in which people are made miserable because the end of jobs has made them feel useless. (I cite the novel myself in [*Four Futures*](https://www.versobooks.com/books/1847-four-futures), although I attempt to mount something of a post-work critique of the story.)

This has certain commonalities with the anti-UBI Right, which also sees waged work as inherently valuable and good, although of course only for the lower orders. This can be rooted in a [producerist](https://www.jacobinmag.com/2011/01/hipsters-food-stamps-and-the-politics-of-resentment) view that ""he who does not work, neither shall he eat." But it can also simply be a driven by a desire to cement and preserve hierarchies and class power, a fear that a working class with additional economic security and resource base of a basic income would get up to "voluntary efforts to meet human needs" that are a bit more confrontational and contentious than Charles Murray imagines.

The final point to make about my diagram of the UBI debate is the relationship between its diagonal terms, which also turn out to have certain commonalities. Put simply, the diagonals connect positions that agree on the *effect* of UBI, but disagree about its *desirability*.

Connecting pro-UBI Leftists like Weeks and Gorz with anti-UBI traditional conservatives is the belief that a basic income threatens to erode the work ethic and ultimately undermine the viability of capitalism. It's just that the left thinks that's a good thing. And the overlapping analysis extends to the relations of *reproduction* as well as those of production. Weeks explicitly presents basic income as an historical successor to the demands of the Wages for Housework movement, a way of breaking down patriarchy and the gendered division of labor.

Historical experience with basic income experiments lends some support to this view. Analysis of the 1970s Canadian "Mincome" program, in which a basic income was provided to residents of a Canadian town, [found that](http://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/2001-odyssee-espace/a-guaranteed-annual-income-from-mincome-to-the-millennium/) "Families that stayed together solely for economic reasons were no longer compelled to do so, since individual members could continue to receive the [Guaranteed Annual Income] separately after a marriage breakup." From a feminist pro-UBI perspective, this shows the value of basic income in providing women the wherewithal to escape from bad relationships. But to the conservative UBI critic, the lesson is the opposite, as it shows how basic income can undermine the traditional family.

On our other diagonal, we find again an agreement on consequences and a disagreement on desirability. Charles Murray views Basic Income as a way to stabilize capitalism and remove the distortions and perverse incentives of the bureaucratic welfare state. Daniel Zamora views Basic Income as a way to intensify neoliberalism and remove the hard-won gains of decommodified services of the social democratic welfare state in favor of submerging all social life in market exchange. Unions fear that basic income will undermine solidarity based on organization in the workplace, a result that would no doubt be seen as a benefit by many of basic income's tech industry boosters (as well as nominally pro-labor renegades like [Andy Stern](http://time.com/4412410/andy-stern-universal-basic-income/)).

I've been reading, thinking and writing about Universal Basic Income off and on for over a decade, and in that time my sense of its political significance has shifted considerably. I would still call myself an advocate of UBI, for similarly post-work and feminist reasons as Weeks or Gorz. But as the concept is increasingly co-opted by those with right wing and pro-capitalist motivations, I think it's increasingly important to situate the demand within a "UBI+" vision of expanded services, rather than falling victim to the shortcut thinking that elevates basic income to a "one weird trick" that will transcend political divides and resolve the contradictions of late capitalism.