Keep Socialism Weird

October 29th, 2018 | Published in Everyday life, Feminism, Fiction, Politics, Socialism, xkcd.com/386

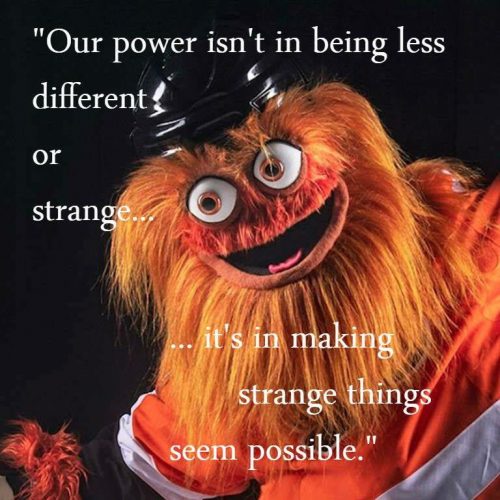

"our power isn't in being less different or strange...it's in making strange things seem possible".

The above statement, though today often attributed to antifa mascot Gritty, was actually made by Kate Griffiths of the Red Bloom Communist Collective. It reiterates themes discussed in a wonderful interview they did with Red Wedge magazine, entitled "Normie Socialism or Communist Transgression".

I've thought about it a lot these past few weeks, through Kavanaugh, the attacks on migrants, the transphobic attacks of the Trump administration, and now the synagogue massacre by a far right anti-semite. And how in each of these cases, I've had to step back and try to really understand how these political events feel to the people directly targeted by them, in contrast to me, who is of course enraged by it all but still feels mostly safe from it.

In particular I'm thinking about something the interviewer mentions, the "cries from some quarters of the Left bleating about transgression, pathologizing broader Left culture --- implicitly queer folks, but others as well, notably cultural producers. . . . the core of the complaint from some circles is that the Left are a bunch of oddballs". This is what Griffiths calls "normie socialism", a belief that we will somehow better relate to the "real working class" if we adapt to its supposedly bourgeois and patriarchal norms rather than running around like a bunch of freaks.

But what is it to be normal? Griffiths notes:

Mostly, it involves being rich enough not to be embarrassed, but it also involves not being too queer; participating in de facto and de jure segregation along lines of race, gender and citizenship in housing and the labor market; getting a job that matches your “potential” or education; or which can afford you signs of stability and affluence. The ideal is a life organized around the moral imperative of providing the best possible future for your children (which you should probably have) or at very least one which keeps you from being “dependent” on your extended family, the state, or other people at all beyond the medium of exchange. But that kind of “normal” is increasingly a pipe dream for anyone who ever had access to it and has always been tenuous-to-unattainable for much of the working class. For some parts of the working class it has always been, in fact, recognized as such and undesirable.

They go on to observe that the normie socialist discourse evades many conversations about the left's historical limitations, the way patrarchial, heterormative, or white supremacist norms and practices have held back organizing and distorted revolutions. And about how being "out" as a communist isn't separate from being out as queer, or trans, say. They all work together. And they're all weird. The vision of this communism isn't just one of traditional nuclear families with nice suburban lives, only with health care and a union and free education and a guaranteed government job.

It's a questioning and recombining of all identities and forms of social life, for which securing the basic physical necessities of life is merely the pre-condition. It's rejecting gender, the family, work as we understand them. It's the radical revaluation of values that, as Jasper Bernes observes in Commune, can be found in both the value form Marxism of Moishe Postone and the science fiction of Ursula LeGuin.

In other words, communism is really, really weird. And I wouldn't have it any other way.

And yet we have liberals and ostensible socialists, the Jonathan Chaits and Angela Nagles and even other writers at Jacobin peddling the fantasy that the alt-right is somehow a consequence of the left being too weird, too queer, too willing to question white supremacy or heteronormativity.

The resurgence of fascism, also documented in Commune, and the horrifying synagogue murders, should finally slam the door on those who want to blame the left for fascism, to pretend that if we just toned it down on Tumblr and got everyone back in the closet, sad boys in the suburbs would flock to us instead of the alt-right. But of course people like Chait and Nagle will keep peddling the same tired old line, as long as people are willing to pay to hear it.

And there are deeper, more important political battles ahead. The most popular socialist podcasts traffick in the supposed normality of themselves and their listeners, even as they flirt with right-leaning transgression in the form of "ironic" racism or anti-semitism. Leading figures in the Democratic Socialists of America seem to be captivated by a paranoid fixation on a supposed plague of "wokeness" and "identity politics", which they are certain will reduce a resurgent American socialism to solipsistic white-guilt struggle sessions if not ruthlessly supressed.

But what does it mean to take our weirdness seriously as political practice? The Le Guin and Postone idea can sound abstract and moralistic, detached from the concrete work of politics. But for me, it amounts to consciously trying to weird my politics and myself.

I am, in certain respects, pretty "normie": straight, cis, white, middle class, the stereotype of a DSA socialist. The point of saying this is not to navel-gaze or self-flagellate or essentialize identity categories, much as the anti-identitarians want to misrepresent it that way. It is to do the opposite, in fact---to try to trouble those categories and get weird. I can't change the advantages my social location gave me, and in fact I want to put them to use for the revolution. What I can do is try to spend more time in spaces that aren't full of people like me, and more time trying to develop political empathy, to see what being a transfeminist communist means, and what it is to struggle with, and against, identities other than the ones ascribed to me. In the process, I can get a little more weird.

I can, in other words, through listening and understanding, try to approach the kind of psychic mobility that would grant me, as the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu puts it, "a command of the conditions of existence and the social mechanisms which exert their effects on the whole ensemble of the category to

which such a person belongs (that of high-school students, skilled workers,

magistrates, etc.) and a command of the conditions, psychological and social, both associated with a particular position and a particular trajectory in social space." This is not a distraction from socialist or communist politics, it is that politics in practice. I would go so far as to say that without developing this command, good organizing is impossible.

Just as importantly, armed with greater empathy and knowledge, I can bring what I know back to the political work I do, and to the "normies". That means, at a larger scale, making sure that, for example, DSA is getting more involved in things like the International Women's Strike and the Trans Book Bloc, rather than recoiling from them in favor of some supposedly pure, "universalist" "class" politics. It means, at a smaller scale, talking to and encouraging fledgling comrades, whose politics may not have gotten much past the Bernie Sanders campaign, to think and act more radically and more deeply.

That's the way forward because it's ideologically and morally right, but also because it's strategically what is most likely to work. Certainly the anti-woketarian inquisitors in DSA mostly seem to have succeeded in generating a lot of ill will, disillusionment, and anger from people who could have been comrades. It's their excesses, and not some over-investment in being self critical about racism or patriarchy on the left, that I'm worried will drive people away and shatter promising organizing projects.

And as Griffiths argues:

I don’t think it will work on its own terms, that is, simply electing socialists or even more Democrats to office. It relies on an already unrealistic and static account of the commitments and sympathies of working class people, who like me, each have their own individual political stories of change, through relationships, through organization and through action. If any of this works, to the extent that it recruits newly politicized socialists, they aren’t going to stay still; we see that I think in a lot of the political expressions of local DSA chapters and working groups, and in even in the development of the Chapo Trap House fandom, which often exceeds its authors in political sensibility and vision.

In other words, warmed-over minimalist social democracy may get you closer to high tide, but it won't prepare you for what you find when you get there. These days I'm sometimes reminded of the antics of some of the Maoist and Trotskyist students of the 1960s, who thought they could connect with "real" workers by cosplaying as clean-cut, conservatively dressed normies. The real workers, of course, were already quitting their jobs, growing their hair out, and getting into sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Now as then, the times call for a politics and a sensibility that is, as the old line of Lenin's had it, "as radical as reality itself."

Keep Socialism Weird!