Lately, it seems like everyone is [talking about 3-D printers](http://www.wired.com/design/2012/09/how-makerbots-replicator2-will-launch-era-of-desktop-manufacturing/all/). Until recently, these devices have been seen either as novelties or as expensive pieces of equipment suited only for industrial use. Now, however, they are quickly becoming affordable to individuals, and capable of producing a wider range of practical items. Just as the computer became a vector for pervasive file-sharing as soon as cheap PCs and internet connections were widespread, we may soon find ourselves living in a world where cheap 3-D printers allow the dissemination of designs for physical objects through the Internet.

The line between science fiction and reality is moving rapidly. Scroll through [these links](http://boingboing.net/tag/3d-printing) at BoingBoing and you'll see 3-D printers churning out everything from guitars to dolls to keys to a prosthetic beak for a bald eagle.

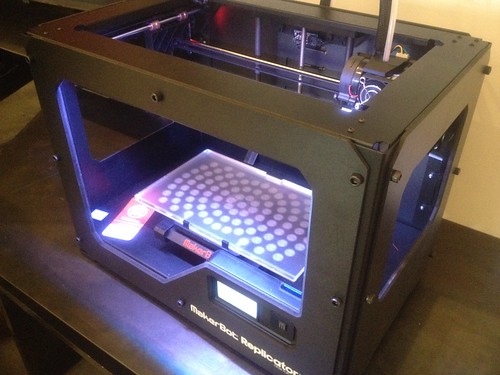

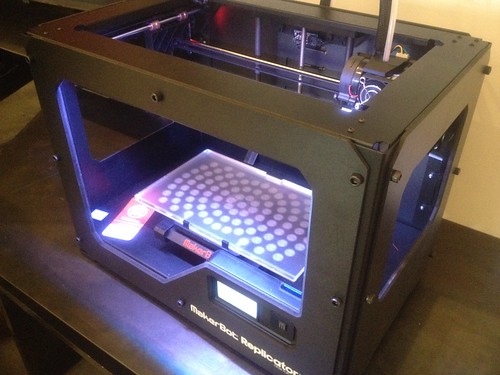

Ensconced in the home, the 3-D printer is a [step toward](http://store.makerbot.com/replicator-404.html) the [replicator](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Replicator_(Star_Trek)): a machine that can instantly produce any object with no input of human labor. Technologies like this are central to the vision of a post-scarcity society that I outlined in ["Four Futures"](http://jacobinmag.com/2011/12/four-futures/). It's a future that could be glorious or terrible, depending on the outcome of the coming political struggles over the adoption of these new technologies. As the title of a [report](http://www.publicknowledge.org/it-will-be-awesome-if-they-dont-screw-it-up) from Public Knowledge puts it, "It will be awesome if they don't screw it up."

Battles over 3-D printing will be fought on two fronts, and two mechanisms of power are likely to be mobilized by the rentier elites who are threatened by these technologies: intellectual property law and the war on terror.

***

I wrote earlier this year (at [Jacobin](http://jacobinmag.com/2012/01/the-google-vanguard/), the [New Inquiry](http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/phantom-tollbooths/), and [Al Jazeera](http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/03/20123121415465844.html)), about the fight over laws like the Stop Online Piracy Act, which would have given the state broad and ambiguous powers to monitor and persecute alleged copyright infringers. The intellectual property lobby is currently in retreat on this front, but the general problem of intellectual property stifling progress has not abated. Aaron Swartz, who was the victim of one of the [more ludicrous](http://jacobinmag.com/2011/07/artificial-scarcity-watch-jstor-edition/) recent piracy busts, is still facing [multiple felony counts](http://crookedtimber.org/2012/09/19/new-charges-against-aaron-swartz/). Apple and Google, meanwhile, now spend [more money on patent purchases and lawsuits](http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/08/technology/patent-wars-among-tech-giants-can-stifle-competition.html) than they do on research and development. And the next front in the war over IP is likely to [center on 3-D printing](http://techcrunch.com/2012/08/26/the-next-battle-for-internet-freedom-could-be-over-3d-printing/).

Like the computer, the 3-D printer is a tool that can rapidly dis-intermediate a production process. Computers allowed people to turn a downloaded digital file into music or movies playing in their home, without the intermediary steps of manufacturing CDs or DVDs and distributing them to record stores. Likewise, a 3-D printer could allow you to turn a digital blueprint (such as a CAD file) into an object, without the intermediate step of manufacturing the object in a factory and shipping it to a store or warehouse. While 3-D printers aren't going to suddenly make all of large-scale industrial capitalism obsolete, they will surely have some very disruptive effects.

The people who were affected by the previous stage of the file-sharing explosion were cultural producers (like musicians) who create new works, and the middlemen (like record companies) who made money selling physical copies of those works. These two groups have interests that are aligned at first, but are ultimately quite different. Creators find their traditional sources of income undermined, and thus face the choice of allying with the middlemen to shore up the existing regime, or else attempting to forge alternative ways of paying the people who create culture and information. But while the creators remain necessary, a lot of the middlemen are being made functionally obsolete. Their only hope is to maintain artificial monopolies through the draconian enforcement of intellectual property, and to win public support by presenting themselves as the defenders of deserving artists and creators.

This same dynamic will arise with 3D printing. Now, however, it is industrial designers who will be cast into the role of the artists and writers, while certain industrial manufacturers will be threatened with death by dis-intermediation. Designers will still be needed to create the patterns that are then fed into 3D printers, while the factories will be superfluous. Imagine a world in which you could download the blueprints for an iPhone 5, and print one out at home. Suddenly, Foxconn and the Apple Store are out of the picture---the only indispensable part of the Apple infrastructure is industrial designers like [Jonny Ive](http://designmuseum.org/exhibitions/online/jonathan-ive-on-apple/jonathan-ives-biography), who are responsible for the putting together the sleek and attractive design of the device. The Public Knowledge report cited above predicts that "as 3D printing makes it possible to recreate physical objects, manufacturers and designers of such objects will increasingly demand 'copyright' protection for their functional objects."

In the last issue of *Jacobin*, Colin McSwiggen [admonished designers](http://jacobinmag.com/2012/08/designing-culture/) to pay attention to the fact that they "make alienated labor possible". The idea of "design" as separate from production is tied to the rise of large scale capitalist manufacturing, when skilled craftspeople were replaced with factory workers repetitively churning out copies from an original pattern. But the order McSwiggen critiques is one which will be undermined by the dissemination of micro-fabrication technology.

3-D printing isn't going to restore the old craft order, in which design and production are united in a single individual or workshop. What it will do instead is make some designers more like musicians, struggling to figure out how to react to consumers who are trading, remixing, and printing their creations all over the place. At the same time, it will blur the line between creation, production, and consumption, as amateurs delve into creating and repurposing design. Like musicians, professional designers will have to decide whether to [scold their customers](http://www.spinner.com/2012/06/19/cracker-david-lowery-npr-illegal-downloading/) and join industrial interests in fighting for strong copyright protections on designs, or whether to look for [new ways of getting paid](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/reports/the-artistic-freedom-voucher-internet-age-alternative-to-copyrights/) and new ways of connecting with their fans.

***

The dark side of being able to print any physical object is that other people can print any physical object. It's all well and good when people are just making clothes or auto parts, but recently there have been stories about more unsettling possibilities, like 3-D printed guns. The first of these was ultimately [over-hyped](http://www.zdnet.com/no-you-cant-download-a-gun-from-the-internet-7000002108/), but did show that the day was at least approaching when home-printed firearms would be a reality. Then, there came a story about a 3-D printer company [revoking its lease and demanding its device back](http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/10/3d-gun-blocked/) after it got wind of a collective that intended to make and test a 3-D printed weapon.

This story is significant because it indicates a line of attack that will be used to restrict access to 3-D printing technologies in general. I have no particular love for the gun-enthusiast crowd. Those leftists who think access to guns is somehow useful to revolutionaries are living in the past and underestimate the physical power of the modern state, and having your own gun is more likely to lead to you getting shot with it than anything else. But guns, and other dangerous objects, will surely be used as the pretext for a much wider crackdown on the free circulation of designs and 3-D printing technology.

When the copyright cartels were still only trying to control the circulation of immaterial goods like music and software, they faced the problem that it was hard to convince people that file sharing was really hurting anyone. Notwithstanding a few lame attempts to [link piracy to terrorism](http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20080328/122324685.shtml), the best they could do was point to the potential loss of income for some artists, and the possibility that there would be less creative work at some point in the future. These same arguments will no doubt be rolled out again, but they will be much more powerful when linked to fearmongering about DIY-printed machine guns and anthrax.

This is where the [intensification of the surveillance state](http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1680390), throughout the Bush and Obama administrations and under the rubric of the "war on terror", becomes important. The post-9/11 security state has gradually rendered itself permanent and disconnected itself from its original justification. We will be told that our purchases and downloads must all be monitored in order to prevent evildoers from printing arsenals in their living rooms, and it will just so happen that this same authoritarian apparatus will be used to enforce copyright claims as well. Meanwhile, the military will of course proceed to use the new technologies to [facilitate their pointless wars](http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/10/printers/). Readers who are interested in a preview of this dystopia of outlaw fabricators trying to outrun the police are referred to Charles Stross's novel, [*Rule 34*](http://www.amazon.com/Rule-34-Charles-Stross/dp/B004Y3I6XW/charlieswebsi-20).

There really *are* dangers in the strange new world of 3-D printing. I'm as uneasy as anyone would be about unbalanced loners printing anthrax in their bedrooms. But we have seen all too well that the repressive state apparatus that promises to keep us safe from terror mostly manages to [roll up a bunch of inept patsies](http://www.propublica.org/article/fact-check-how-the-nypd-overstated-its-counterterrorism-record) while remaining unable or unwilling to stop a [deranged massacre](http://www.salon.com/2012/10/01/aurora_survivor_stars_in_gun_control_ad/) from going down now and then.

Terrorism, like drugs before it, is only a pretext for ratcheting up a repressive apparatus that will be used for other purposes. Today, we are familiar with the statistics [showing that](http://walt.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2012/10/02/what_id_like_to_ask_obama_and_romney) terrorism has killed 32 Americans per year since 9/11, while gun violence has killed 30,000. Soon enough we will be able to add 3-D printers to the list of phantom menaces that are trotted out to justify wiretaps, raids, and indefinite detentions.

***

William Gibson famously said that the future is already here, it's just unevenly distributed. In the future, expect the copyright cartels and the national security state to team up to bring you a new announcement: the future is here, but you're not allowed to have it.