The United States Makes Things

April 4th, 2011 | Published in Political Economy, Social Science, Statistical Graphics, Work | 4 Comments

The other day I got involved in an exchange with some political comrades about the state of manufacturing in the United States. We were discussing this Wall Street Journal editorial, which laments that "more Americans work for the government than work in construction, farming, fishing, forestry, manufacturing, mining and utilities combined". Leaving aside the typical right-wing denigration of government work, what should we think about the declining share of of Americans working in industries that "make things"?

I've written about this before. But I'm revisiting the argument in order to post an updated graph and also to present an alternative way of visualizing the data.

Every time I hear a leftist or a liberal declare that we need to create manufacturing jobs or start "making things" again in America, I want to take them by the collar and yell at them. Although there is a widespread belief that most American manufacturing has been off-shored to China and other low-wage producers, this is simply not the case. As I noted in my earlier post, we still make lots of things in this country--more than ever, in fact. We just do it with fewer people. The problem we have is not that we don't employ enough people in manufacturing. The problem is that the immense productivity gains in manufacturing haven't accrued to ordinary people--whose wages have stagnated--but have instead gone to the elite in the form of inflated profits and stock values.

Anyway, I'm revisiting this because I think everyone on the left needs to get the facts about manufacturing employment and output burned into their memory. The numbers on employment in manufacturing are available from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, and the data on output is available from the national Federal Reserve site. Here's an updated version of a graph I've previously posted:

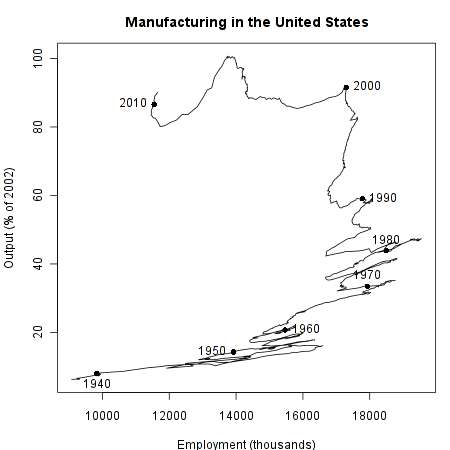

I like this graph a lot, but today I had another idea for how to visualize these two series. Over at Andrew Gelman's blog, co-blogger Phil posted an interesting graph of bicycing distance and fatalities. That gave me the idea of using the same format for the manufacturing data:

This graph is interesting because it seems to show three pretty different eras in manufacturing. From the 1940's until around 1970, there was a growth in both employment and output. This, of course, corresponds to the "golden age" of post-war Keynesianism, where the labor movement submitted to capitalist work discipline in return for receiving a share of productivity gains in the form of higher wages. From 1970 until around 2000, output continues to rise rapidly, but employment stays basically the same. Then in the last ten years, employment falls dramatically while output remains about the same.

This big take-home point from all this is that manufacturing is not "in decline", at least in terms of output. Going back to an economy with tons of manufacturing jobs doesn't make any more sense than going back to an economy dominated by agricultural labor--due to increasing productivity, we simply don't need that many jobs in these sectors. Which means that if we are going to somehow find jobs for 20 million unemployed and underemployed Americans, we're not going to do it by building up the manufacturing sector.

April 4th, 2011 at 4:30 pm (#)

This is a very interesting and useful summary. I, too, have wanted grab a liberal collar at times, but I also think the nostalgic response is understandable. Given that U.S. manufacturing has become less labor-intensive, its outputs are no longer as visible in everyday life. I went to a Goodwill store in Connecticut a few years ago, and many of the old (“vintage”) clothes I looked at were made in Connecticut. I was really surprised, because you don’t see any signs of a garment industry anywhere, but judging by the items in the store, it must have been alive and well as recently as 30-40 years ago. So when people say we need to stark “making things” again, they probably mean these kinds of items of everyday use—the kinds of things you can buy in Williamsburg hipster boutiques—not heavy machinery or other capital-intensive products.

April 5th, 2011 at 9:22 am (#)

This is a good point, and I guess there are two separate things going on with people lamenting the decline of manufacturing. One is the kind of phenomenological connection to manufactured objects that you mention, which manifests as a yearning for some kind of unmediated connection to producing the items of everyday life. It’s a cry against the fetishism of the commodity, in a way. (But I see it as ultimately a conservative impulse–as in that recent book “Shop Class as Soulcraft”.)

This is distinct from the attempt to envision a future economy that is less unequal and that can address the stagnation of employment and income growth in the neoliberal era. My polemic was against people who present manufacturing as the solution to that issue.

But in any case, both of these perspectives run up against the same problem: after all, clothing and furniture production are subject to technologically-driven accelerations in productivity too, though not as much as heavy machinery. So whether your problem is alienation or lack of good jobs, it’s hard to present manufacturing as the solution unless you’re willing to take a radical stand against labor-saving technology, and in favor of lower material standards of living.

June 21st, 2011 at 12:22 pm (#)

[…] things” in America again, we could solve our unemployment problem. The reality is that we already make plenty of things, and the decline of manufacturing jobs is due more to technology than to off-shoring. The U.S. […]

September 15th, 2011 at 12:48 pm (#)

Thank you for pointing out the obvious. A lot (not all) of the talk about “bringing back” manufacturing jobs comes from Democratic Party politicians who are suffering electorally from the decline of the unions whose leaders haven’t met a Dem they didn’t support since the 1930s (well, except maybe SEIU when they backed Pataki). This filters downward to liberals and rank-and-file workers as well, particularly those who have had their work outsourced, moved offshore, or whose jobs have been eliminated by mechanization (steelworkers, autoworkers in Detroit).

Do you count construction as part of manufacturing (would the alternative be to put them into the service sector if not)? There are an awful lot of schools and other infrastructure projects that need to be done that would help boost employment.