Making things, marking time

January 27th, 2010 | Published in Data, Political Economy, R, Work | 1 Comment

Today Matt Yglesias revisits a favorite topic of mine, the distinction between U.S. manufacturing employment and manufacturing production. It has become increasingly common to hear liberals complain about the "decline" in American manufacturing, and lament that America doesn't "make things" anymore:

Harold Meyerson had a typical riff on this recently:

Reviving American manufacturing may be an economic and strategic necessity, without which our trade deficit will continue to climb, our credit-based economy will produce and consume even more debt, and our already-rickety ladders of economic mobility, up which generations of immigrants have climbed, may splinter altogether.

. . .

The epochal shift that's overtaken the American economy over the past 30 years . . . finance, which has compelled manufacturers to move offshore in search of higher profit margins . . . retailers, who have compelled manufacturers to move offshore in search of lower prices for consumers and higher profits for themselves

. . .

Creating the better paid, less debt-ridden work force that would emerge from a shift to an economy with more manufacturing and a higher rate of unionization would reduce the huge revenue streams flowing to the Bentonvilles (Wal-Mart's home town) and the banks . . . . The campaign contributions from the financial sector to Democrats and Republicans alike now dwarf those from manufacturing -- a major reason why our government's adherence to free-trade orthodoxy in what is otherwise a mercantilist world is likely to persist.

. . .

[Sen. Sherrod] Brown . . . acknowledges that as manufacturing employs a steadily smaller share of the American work force, "younger people probably don't think about it as much" as their elders . . . . Politically, American manufacturing is in a race against time: As manufacturing becomes more alien to a growing number of Americans, its support may dwindle, even as the social, economic, and strategic need to bolster it becomes more acute. That makes push for a national industrial policy -- to become again a nation that makes things instead of debt, to build again our house upon a rock -- even more urgent.

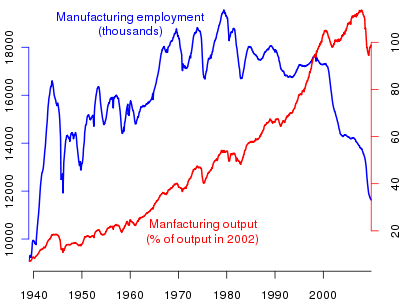

I don't dispute that manufacturing has become "more alien" to the bulk of American working people. But I question Meyerson's explanation for why this has happened, and I wonder whether we should really be so horrified by it. The evidence suggests that the decline in manufacturing employment in this country has been driven not primarily by offshoring (as Meyerson would have it), but by a dramatic increase in productivity. Yglesias provides one graphical illustration of this; here is my home-brewed alternative, going back to World War II:

This picture leaves some unanswered questions, to be sure. First, one would want to know what kind of manufacturing has grown in the U.S., for one thing; however, my cursory examination of the data suggests that U.S. output is still more heavily oriented toward consumer goods over defense and aerospace production, despite what one might think. Second, it's possible that the globally integrated system of production is "hiding" labor in other parts of the supply chain, in China and other countries with low labor costs.

But I don't think the general story of rapidly increasing productivity can be easily ignored. To really reverse the decline in manufacturing employment, we would need to have something like a ban on labor-saving technologies, in order to return the U.S. economy to the low-productivity equilibrium of forty or fifty years ago. Of course, that would also require either reducing American wages to Chinese levels or imposing a level of autarchy in trade policy beyond what any left-protectionist advocates.

Needless to say, I think this modest proposal is totally undesirable, and I raise it only to suggest the folly of "rebuilding manufacturing" as a slogan for the left. As Yglesias observes in the linked post, manufacturing now seems to be going through a transition like the one that agriculture experienced in the last century: farming went from being the major activity of most people to being a niche of the economy that employs very few people. Yet of course food hasn't ceased to be one of the fundamental necessities of human life, and we produce more of it than ever.

And yet I understand the real problem that motivates the pro-manufacturing instinct among liberals. The decline in manufacturing has coincided with a massive increase in income inequality and a decline in the prospects for low-skill workers. Moreover, the decline of manufacturing has coincided with the decline of organized labor, and it is unclear whether traditional workplace-based labor union organizing can ever really succeed in a post-industrial economy. But the nostalgia for a manufacturing-centered economy is an attempt to universalize a very specific period in the history of capitalism, one which is unlikely to recur.

The obsession with manufacturing jobs is, I think, a symptom of a larger weakness of liberal thought: the preoccupation with a certain kind of full-employment Keynesianism, predicated on the assumption that a good society is one in which everyone is engaged in full-time waged employment. But this sells short the real potential of higher productivity: less work for all. As Keynes himself observed:

For the moment the very rapidity of these changes is hurting us and bringing difficult problems to solve. Those countries are suffering relatively which are not in the vanguard of progress. We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come-‑namely, technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.

But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem. I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is to‑day. There would be nothing surprising in this even in the light of our present knowledge. It would not be foolish to contemplate the possibility of afar greater progress still.

. . .

Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem‑how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.

Productivity has continued to increase, just as Keynes predicted. Yet the long weekend of permanent leisure never arrives. This--and not deindustrialization--is the cruel joke played on working class. The answer is not to force people into deadening make-work jobs, but rather to acknowledge our tremendous social wealth and ensure that those who do not have access to paid work still have access to at least the basic necessities of life--through something like a guaranteed minimum income.

Geeky addendum: I thought the plot I made for this post was kind of nice and it took some figuring out to make it, so below is the R code required to reproduce it. It queries the data sources (A couple of Federal Reserve sites) directly, so no saving of files is required, and it should automatically use the most recent available data.

manemp <- read.table("http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/MANEMP.txt",

skip=19,header=TRUE)

names(manemp) <- tolower(names(manemp))

manemp$date <- as.Date(manemp$date, format="%Y-%m-%d")

curdate <- format(as.Date(substr(as.character(Sys.time()),1,10)),"%m/%d/%Y")

outputurl <- url(paste(

'http://www.federalreserve.gov/datadownload/Output.aspx?rel=G17&series=063c8e96205b9dd107f74061a32d9dd9&lastObs=&from=01/01/1939&to=',

curdate,

'&filetype=csv&label=omit&layout=seriescolumn',sep=''))

manout <- read.csv(outputurl,

as.is=TRUE,skip=1,col.names=c("date","value"))

manout$date <- as.Date(paste(manout$date,"01",sep="-"), format="%Y-%m-%d") par(mar=c(2,2,2,2)) plot(manemp$date[manemp$date>="1939-01-01"],

manemp$value[manemp$date>="1939-01-01"],

type="l", col="blue", lwd=2,

xlab="",ylab="",axes=FALSE, xaxs="i")

axis(side=1,

at=as.Date(paste(seq(1940,2015,10),"01","01",sep="-")),

labels=seq(1940,2015,10))

text(as.Date("1955-01-01"),17500,

"Manufacturing employment (millions)",col="blue")

axis(side=2,col="blue")

par(new=TRUE)

plot(manout$date,manout$value,

type="l", col="red",axes=FALSE,xlab="",ylab="",lwd=2,xaxs="i")

text(as.Date("1975-01-01"),20,

"Manfacturing output (% of output in 2002)", col="red")

axis(side=4,col="red") |

October 25th, 2010 at 3:52 pm (#)

[…] certainly real, it is not the most important driver of de-industrialization. For the truth is that the physical output of the U.S. manufacturing sector is far higher today than it was forty years ago, even though the number of workers in manufacturing has declined […]