Eight Hours For What They Will

May 30th, 2011 | Published in Art and Literature, Time, Work

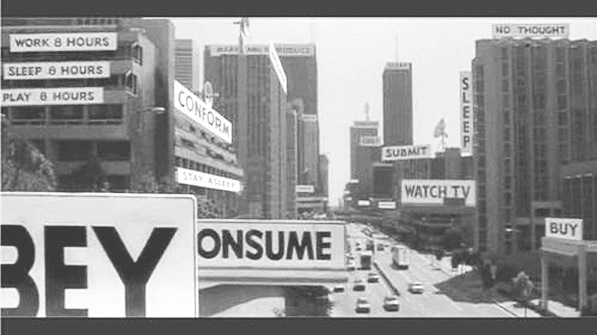

The other day I re-watched John Carpenter's [*They Live*](http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0096256/)--which, for the record, is a pretty good satire of Reagan-era America, and deserves to be remembered for more than just that stupid Shepard Fairey [sticker campaign](http://obeygiant.com/). While watching, I noticed something pretty great that I missed the first time through. It shows up after the main character puts on magic sunglasses, which allow him to see that the billboards around him actually contain secret brainwashing messages. Most of these just say things like "consume" and "obey". But check out the sign in the upper left corner of this picture:

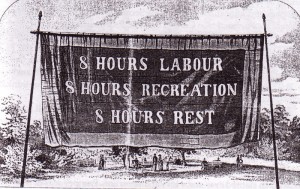

That command, of course, is a riff on an old slogan of the 19th century labor movement, which demanded the eight-hour day using signs like this one:

As David Roediger and Philip Foner remark in their [great history of American labor and the working day](http://books.google.com/books?id=h8P-uuyYe_YC&lpg=PA324&ots=xG4cd8F4rn&dq=roediger%20foner&pg=PA98#v=onepage&q&f=false):

> [T]he cry "Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for recreation," acted as more than a common denominator. It embodied . . . the highest aspirations of the working population. It expressed cherised values. . . . In making the eight-hour system the key to equal education for children, to the continued mental development of adults, to the defense of republican virtue and class interest by an enlightened and politically active citizenry, to health, to vigor, and to social life, supporters viewed their demand as an initial step to major changes, not as a niggling reform. (pp. 98-99)

As is well known, the demand for shorter hours mostly disappeared from organized labor's agenda after World War II, for [complex](http://books.google.com/books?id=lv9cfP1QMAcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false) and [disputed](http://books.google.com/books?id=yV2xgJBNfo4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=cutler+uaw+hours&hl=en&ei=edPjTZqZAoPq0gH07Z2yBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false) reasons. The sign I saw in *They Live* is one consequence of abdicating the postive class argument for shorter hours. By the time the movie was made in 1988, the eight-hour movement's greatest slogan could come to seem not like a cherished victory of the working class, but rather as a piece of dystopian propaganda. "Eight hours recreation" becomes the command to "play eight hours", and this "play" is refigured as obligatory participation in consumerist culture rather than the opportunity for political, intellectual and moral development that it signified for the eight-hour campaigners. Perhaps it's not surprising, then, that these days long hours are often portrayed as an issue of individual preferences or "workaholic" psychology, rather than the outcome of organized labor's long political defeat.

I have a feeling this little vignette will end up in my dissertation somehow, although I don't think I mentioned doing any cultural studies in my fellowship proposal.