Failure Mode

November 2nd, 2011 | Published in Political Economy, Politics

It's [general strike day](http://zunguzungu.wordpress.com/2011/11/01/the-day-before-the-day-of-action/) in Oakland. I don't really know what to expect---this isn't going to be a true general strike in the sense of completely shutting down the city like [in 1946](http://ufcw324.org/About_Us/Mission_and_History/Labor_History/Oakland_General_Strike__A_Worker%E2%80%99s_Holiday/), but it could still be an exciting step forward. And since I've underestimated the impact of everything that's happened since the beginning of Occupy Wall Street, I won't make any confident predictions until I see what happens in the streets. But one big wild card, once again, is the response of the Mayor and the police.

What's been remarkable about the events in Oakland and elsewhere, so far, is how much they've freaked out and disrupted the political system. For my whole life, it seemed like the governing elite could easily get rid of mass protest through some judicious mixture of ignoring and repressing demonstrators. But that seems not to be working this time. When Michael Bloomberg tried to sweep away the Wall Street occupation under the pretext of "cleaning" the park, he was met with thousands of solidarity protestors and forced to back down. When the Oakland police tried to gas their city's occupation into submission, they not only made a martyr out of Scott Olsen, but felt they had to issue a bizarre [open letter](http://www.opoa.org/uncategorized/an-open-letter-to-the-citizens-of-oakland-from-the-oakland-police-officers%E2%80%99-association/) in which they distanced themselves from their own violent actions. In Albany, the police simply [defied](http://thinkprogress.org/special/2011/10/24/352228/albany-police-defy-orders-and-refuse-to-arrest-occupy-albany-protesters-these-people-were-not-causing-trouble/) the governor and mayor's order to evict protestors. In Tennessee, the state government first tried to dispel protests with mass arrests, but then [declined to defend](http://www.nashvillescene.com/pitw/archives/2011/10/31/state-concedes-defeat-in-occupy-nashville-battle-judge-bans-more-arrests) the policy in the face of a court injunction.

In all these cases, it seems that the system is incapable of handling the appearance of any kind of mass civic participation that doesn't go through the expected channels---and this problem is not limited to the United States. The European Union's attempts to contain its banking crisis are, it seems, not robust to the outbreak of democracy, since Greece's Prime Minister was able to plunge the continent into turmoil by merely threatening to [give his people a say](http://www.salon.com/2011/11/01/greek_bailout_wall_street/) in the current bailout and austerity plan for the country. In Britain, an occupation has [set off crisis](http://www.periscopepost.com/2011/11/occupy-london-claims-another-church-victim-as-knowles-resigns-st-pauls-in-turmoil/) and resignations in the Church of England, while directing uncomfortable attention to the [bizarre and authoritarian structure](http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/oct/31/corporation-london-city-medieval) that runs central London. What's going on here?

A clue, I think, is to be found in a remark that comes near the end of David Graeber's recent [magnum opus on debt](http://mhpbooks.com/books/debt/):

> The last thirty years have seen the construction of a vast bureaucratic apparatus for the creation and maintenance of hopelessness, a giant machine designed, first and foremost, to destroy any sense of possible alternative futures. At its root is a veritable obsession on the part of the rulers of the world . . . with ensuring that social movements cannot be seen to grow, flourish, or propose alternatives; that those who challenge existing power arrangements can never, under any circumstances, be perceived to win.

In this, Graeber is echoing one of my favorite, often-quoted lines from [Fredric Jameson](http://books.google.com/books?id=sPBad_aN0i0C&pg=PA229&dq=jameson+%22hegemonic+ideology+of+the+system%22&hl=en&ei=UwWxTp-4Kc6UOpmvyf4B&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false): "The mass of people . . . do not themselves have to believe in any hegemonic ideology of the system, but only to be convinced of its permanence." This was the outlook that Margaret Thatcher enunciated in one of her [famous speeches](http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/process-analysis-tools/overview/fmea.html):

> If I could press a button and genuinely solve the unemployment problem, do you think that I would not press that button this instant? Does anyone imagine that there is the smallest political gain in letting this unemployment continue, or that there is some obscure economic religion which demands this unemployment as part of its ritual? This Government are pursuing the only policy which gives any hope of bringing our people back to real and lasting employment.

This outlook is commonly summarized as "There Is No Alternative". From this starting point, one can create a method of rule which does not depend on being positively affirmed or seen as legitimate by most people, but merely requires the resigned assent of a demoralized populace. Thus the rule of the financial elites can continue, even as political legitimacy is [drained out](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/09/politicizing-the-fed/) of the institutions of government. But if you build a system on the assumption that there will be no dissent and no alternatives, what happens when dissent *does* appear, and begins to articulate alternatives? I submit that we're seeing what happens, in the Occupy Wall Street protests and beyond: the basic fragility and brittleness of neoliberal politics is being exposed. That fragility is analogous to the precariousness of neoliberal economics, and it arises for some of the same reasons.

Contemporary capitalism, we are often told, is characterized by the relentless pursuit of *efficiency*. In one telling, a more efficient economy is one that gets more output out of the same amount of labor and resources. But from another perspective, a streamlined and ultra-efficient economy is one which produces more and faster in normal times, but which can only do so by cutting out the safeguards and redundancies that protect the system from catastrophic failure when things go bad. Thus the global economy becomes simultaneously more dynamic and more fragile. As Felix Salmon [puts it](http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/04/18/the-implications-of-a-downgraded-us/), "as a general rule, the more efficient something is, the easier it is to break." Both the economics and the politics of neoliberalism are turning out to be very efficient and very easy to break.

To take a metaphor from engineering, capitalist societies of an earlier era were somewhat over-engineered. Before precise computer models were available, the builders of physical infrastructure built works that were [far more robust](http://www.freakonomics.com/2007/10/22/viva-las-vegas-seriously/) than they needed to be. This uses up more labor and materials, but it also makes structures more resistant to failure; thus, older bridges like those in New York City can stay standing even when they are neglected for years, while more recent structures can collapse in [catastrophic fashion](http://ezinearticles.com/?Insights-Into-the-Minneapolis-Bridge-Collapse&id=675460).

This same logic can be applied to the economy. The creation of a globalized, just-in-time, streamlined supply chain has made possible huge gains in the efficiency of manufacturing and distribution. Yet as [Barry Lynn](http://www.thenation.com/article/162317/how-america-could-collapse) has [argued](http://rortybomb.wordpress.com/2011/04/11/barry-lynn-at-inet-decoupling-our-corporations/), it also makes the entire global economy vulnerable to localized shocks, as when a Japanese earthquake crippled world-wide production of Toyota automobiles, or when an earthquake in Taiwan [led to a global shortage](http://www.deseretnews.com/article/722921/Computer-prices-on-rise-amid-chip-shortage-Taiwan-quake-is-most-recent-blow-to-ailing-industry.html) of computer memory.

And what goes for manufacturing goes double for finance. Investment banks, players in global markets who intricately hedge their positions in order to maximize their ability to take on risk, are uniquely vulnerable to economic shocks. As the saying goes, "in a crisis, all correlations go to 1". Using another engineering concept, "tight coupling", [Richard Bookstaber](http://rick.bookstaber.com/2007/09/myth-of-noncorrelation.html) explains the process, showing how disruptions in one corner of the financial markets can quickly propagate into a major worldwide crisis.

The tradeoff between efficiency and stability that exists in the process of production and circulation is also present in the [mode of regulation](http://lipietz.net/spip.php?article750). If the output of capitalist production is commodities, the output of the political system is social order and the consent of the working class. This latter, too, can be produced with either more or less efficiency. In the mid-20th century, capitalist economies developed welfare-state mechanisms for dealing with economic polarization and political unrest, and thereby securing some social stability. Keynesian capitalism's [failure mode](http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/process-analysis-tools/overview/fmea.html) was one in which working class dissatisfaction could be expressed through unions and labor parties; taxation and redistribution could be used to prop up demand, buy off the working class, and head off more radical forms of political dissent.

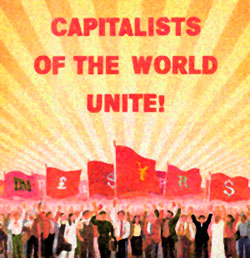

However, such a system is expensive for the capitalist class, in terms of both money and social power---eventually, the bourgeoisie concluded it would be more efficient to simply [keep all the surplus for themselves](http://www.peterfrase.com/2011/10/labors-share-in-cross-national-perspective/) and rely on hopelessness to keep the rabble in line. Thus neoliberalism has systematically dismantled the supports and failsafe systems that kept dissent in check, and has relied instead on preventing dissent from arising in the first place. The 99% have been cut off from institutional channels for influencing policy or voicing their grievances, and thus have been left with no choice but to take it to the streets. And now that we have done so, we are seeing the chaotic and unpredictable failure mode of neoliberal governance.

Since the end of the housing bubble, a lot of people have been looking for the next bubble to collapse. Maybe we've been living through a bubble in political order, a AAA-rated social stability which is turning out to be based on much riskier and more insecure foundations than any of its architects believed.