Manufacturing Output Around the World

April 11th, 2011 | Published in Political Economy, Statistical Graphics, Work

I went into excruciating detail about manufacturing output statistics in my last post, mainly so that I could post some more analysis using various international sources. One question that often comes up about American manufacturing, after all, is whether our pattern of deindustrialization is unusual compared to other countries. To get some idea, we can use the statistics on employment and output compiled by the OECD. These numbers are, as best I can tell, roughly comparable to the Federal Reserve "output" numbers I used in my initial post on U.S. manufacturing.

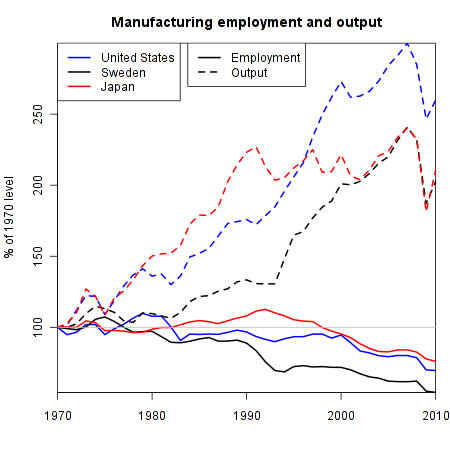

For most countries, the OECD data only goes back a few years. So for some of the most interesting cases--namely, recently industrializing poor countries--we don't have good historical data. However, we can at least compare the U.S. to other rich countries. Here's manufacturing employment and output for the U.S., Sweden, and Japan, going back to 1970:

Here, we see that "deindustrialization" in the sense of declining manufacturing employment is not just a U.S. phenomenon. Likewise, manufacturing output has grown dramatically in all three countries. Indeed, output growth has been faster in the U.S.

This is particularly amusing with respect to Japan. Back in the 1980's, of course, Japan played the role of bête noir in American popular discourse that China plays today: the scary Asian menace that was going to out-compete the U.S. economy and ensure our economic doom. And indeed, output and employment in manufacturing both grew faster in Japan than in the U.S. in the 1980's. But since then, Japan has followed the same pattern of employment decline as the United States, while its output has remained stagnant. This is worth keeping in mind when considering the likely future of manufacturing in today's low-wage countries.

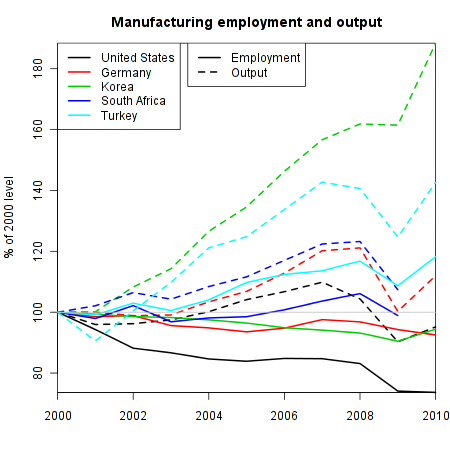

But what if we expand our view to include some more recently industrialized countries? Given the available data, we are unfortunately limited to just the most recent business cycle. Still, there are some interesting patterns:

Now some different patterns emerge. The U.S., Germany and especially Korea show the pattern of divergence between employment and output. In South Africa and Turkey, on the other hand, the two are more closely linked. Turkey, in fact, shows an actual increase in the number of manufacturing employees, unlike any of these other countries. This is likely due to a combination of low Turkish wages and proximity to EU markets--along with the anticipation of possible future Turkish membership in the EU. There are those who would like to "bring back" manufacturing jobs from offshore locations like Turkey. But it's not clear how many jobs this would actually create--Turkish manufacturing is a big employer precisely because it isn't all that productive. Protectionist policies--or increases in wages in the low-wage producers--would probably create some jobs in the rich countries, but they would also probably lead to increased use of labor-saving technology.

Of course, we still haven't dealt with the panda bear in the middle of the room: China. But I'm going to wait and put that one in its own post.