In his influential treatise on the modern welfare state, [*The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism*](http://books.google.com/books/about/The_three_worlds_of_welfare_capitalism.html?id=Vl2FQgAACAAJ), Gøsta Esping-Andersen proposed that one of the major axes along which different national welfare regimes varied was the degree to which they de-commodified labor. The motivation for this idea is the recognition--going back to Marx--that under capitalism people's labor-power becomes a commodity, which they must sell on the market in order to earn the means of supporting themselves.

Following Karl Polanyi, Esping-Andersen describes the *de*-commodification of labor as the situation in which "a service is rendered as a matter of right, and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market" (p. 22). So long as the society remains a capitalist one, it is never possible for labor to be *totally* de-commodified, for in that circumstance there would be nothing to compel workers to go take a job working for someone else, and capital accumulation would grind to a halt. However, insofar as there are programs like unemployment protection, socialized medicine, and guaranteed income security in retirement--and insofar as eligibility for these programs is close to universal--we can say that labor has been partially de-commodified. On the basis of this argument, Esping-Andersen differentiates those welfare regimes that are highly decommodifying (such as the Nordic countries) from those in which workers are still much more dependent on the market (such as the United States).

In the lineage of comparative welfare state research following Esping-Andersen, de-commodification is generally discussed in the way I've just presented it: in terms of the state's role in either forcing people into the labor market, or allowing them to survive outside of it. However, from the standpoint of the worker, we can think of the de-commodifying welfare state as giving people a *choice* about whether or not to commodify their labor, rather than forcing them to sell their labor as would be the case in the absence of any welfare-state institutions. The choice that is involved here is not merely about income. It ultimately comes down to how we want to organize our time, and how we want to structure our relations with other people.

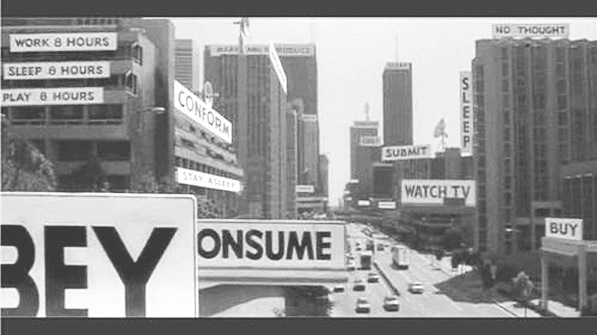

What is ultimately at stake here is not merely the commodification of labor-power, but the commodification of all areas of social life. For based on the institutions that exist and the choices people make within them, we can imagine multiple social equilibria. Social life could be highly commodified: everyone performs labor for others in return for a wage, and also pays others to perform social functions which they don't have time for. But we could have a much lower level of commodification where people work less, because their cost of living is much lower: they are able to satisfy many of their personal needs without spending money.

To elucidate this point, consider a simplified thought experiment. Suppose you and I live in adjacent apartments. Now consider the following ways in which we might satisfy two of our needs: food and a clean habitat.

In scenario A, I cook my own meals and clean my own bathroom, and you do the same for yourself.

In scenario B, you pay me to cook your meals, and I pay you to clean my bathroom.

In scenario C, I pay you to cook for me and clean my bathroom, and you pay me to cook your meals and clean your bathroom.

This hypothetical is a bit silly, since with only two people involved we could just barter the trade in services rather than paying each other money. But in a more complex economy with many people paying each other for things, the medium of exchange becomes necessary, so I leave that element in place even in this simplified example.

What might make each of these three scenarios desirable?

The advantage of scenario A is that each of us has maximal control over our labor and our lives. I cook and clean when I choose, I eat just what I like, and I will do just enough cleaning to ensure that the bathroom meets my standards of cleanliness.

The advantage of scenario B is that it might be more efficient, if each of us has what economists call "comparative advantage" in one of the tasks. If I'm a better cook, but you're better at cleaning, then each of us ends up with overall better meals and cleaner bathrooms than we would have had otherwise. The downside, however, is that each of us has now partly alienated our labor to some degree. I have to monitor you to make sure that you're doing a complete job of cleaning, and you can boss me around if you dislike my food or I don't have dinner ready on time. What's more, the only way for this exchange to be fair to both of us is in the unlikely event that you enjoy cleaning the bathroom just as much as I like cooking. In the more likely case that both of us find cleaning much less pleasant than cooking, you get a raw deal.

Scenario C would seem to combine the worst elements of the other two scenarios. There is no efficiency gain, since we are both performing both tasks. And our labor is maximally alienated, since we are doing all our cooking and cleaning at someone else's command rather than for ourselves.

The point of these examples is that they represent different visions of how the economy might work. Scenario A is the one I sympathize with, and it's one that motivates many socialists, feminists, social democrats, and advocates of shorter working hours and less consumerist ways of living. Scenario B is more like the traditional vision of 20th century liberal capitalism: by commodifying more of social life, we increase our material abundance but at the expense of living alienated lives as commodified labor.

However, I would argue that a lot of political and economic discourse in the United States is actually dominated by the third scenario, which sees commodification as a good in itself, irrespective of its efficiency or its effect on our working lives. I said above that scenario C didn't have anything to recommend it, but this is not exactly true. For in a society where labor-power is still commodified and people are dependent on the labor market, it is essential that we constantly create new jobs for people to perform--otherwise, you end up with mass unemployment just like we're seeing right now. Scenario C is the one that maximizes job-creation and GDP growth, even though it is by no means obvious that it is the scenario that maximizes human happiness and satisfaction.

It's worth belaboring this point precisely because so many liberals and even leftists take the "high-commodification" equilibrium for granted. Take the example of [Matt Yglesias](http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/issue/) of the Center for American Progress. I write about him often (and once got [Yglesiassed](http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/2011/03/23/200322/endgame-419/) in return) because in many ways I find him a more congenial thinker than a lot of more traditional "leftists" who seem trapped in nostalgia for mid-20th century industrial capitalism. But the issue of commodification gets at a core area where we see the world differently.

Yglesias often writes about the fact that industrial employment is inevitably declining for technological reasons, and hence services are bound to make up an increasing share of the employment. This motivates some of his other hobby-horses, such as his crusade against occupational licensing, which he sees as an impediment to creating these needed service jobs. Now, I have no particular attachment to occupational licensing, and on the issue of manufacturing and industrial employment, Yglesias and I are basically in agreement. Where we disagree is in seeing the best future trajectory of the economy as one in which people perform more and more services for each other, for pay. [For example](http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/2011/03/07/200135/the-yoga-instructor-economy/):

> [T]his is why I’ve been saying that yoga instructors have the job of the future. Nothing in these trends suggests that the actual quantity of janitors is going to increase in the future. If anything, falling demand for office workers implies that the future can have fewer. So is the future a smallish number of wealthy office workers served by an "aristocracy of labor" of unionized janitors awash in a pool of unemployed people enjoying free health care? Presumably not. The people of the future will be richer than the people of today, and therefore will more closely resemble annoying yuppies. Nicer restaurants are more labor-intensive than cheap ones, and the further up the scale you go the more specialized skills (think sommelier) come into play. Annoying yuppies take yoga classes, or even hire personal trainers. Artisanal cheese is more labor-intensive to produce than industrial cheese. More people will hire interior designers and people will get their kitchens redone more often. There will be more personal shoppers and more policemen. People will get fancier haircuts.

It's easy to mock the idea that the future economy will be based entirely on giving each other haircuts and yoga instruction. But my objection is not that this is *implausible*--I think it's entirely plausible, and such a world could even feature a relatively egalitarian income distribution, depending on the bargaining power of labor and the intervention of the state. The real question, I think, is whether this is the only way for things to turn out--that is, is it really true that [the yuppie that is richer only shows, to the less rich, the image of their own future](http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p1.htm)? And if not, is it the most desirable outcome?

I don't want to pre-judge this choice so much as just argue that it *is* a choice. Whether we end up in a low-commodification, low cost of living scenario A or a high-commodification, high cost of living scenario C will be the result of an interaction between the state and other institutions and individual choices within those institutions. It is thus both a political and a cultural question. Even now, not every country resolves these questions in the same way. In the Netherlands, for example, both incomes and working hours are lower than in the United States, and a good argument can be made that the well-being of the Dutch is [at least as high as our own](http://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:129022).

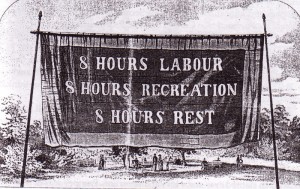

This is why I think that the politics of de-commodification in the 21st century will be closely linked to the politics of time.