The *New York Times* brings us once again to Foxconn and China's manufacturing industry, in [a story](http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/31/business/global/labor-shortage-complicates-changes-in-chinas-factories.html) reporting that "there is a growing shortage of blue-collar workers willing to work in China's factories". This, we are told, is "a big factor in the long shifts and workweeks manufacturers have used to meet production quotas."

The implied model of the labor market here is a strange one indeed. If an important input to production---in this case, workers---is scarce, economic theory suggests that its price will be bid upward. That would mean some combination of higher wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions. Instead, we are supposed to find it logical that a shortage of workers causes bosses to work their employees *harder*.

In what seems to be something of a pattern in NYT labor reporting, the giveaway line is saved for the last paragraph. "It's hard to find a good job," says a young Chinese worker. "It's easy to find just any job." The entire story is now revealed to be a slightly more orientalist version of a U.S. media standby, in which capitalists whine about being forced to offer competitive wages and working conditions. Dean Baker never tires of [lampooning](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/the-problem-of-structrual-unemployment-really-incompetent-managers) these [stories](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/washington-post-reports-on-incompetent-managers-in-manufacturing-industry), which credulous reporters continually trot out as an explanation for high unemployment.

My favorite recent example of this phenomenon was the flurry of coverage surrounding Alabama's anti-immigrant laws, which had the effect of driving many undocumented workers out of the state. This produced, among other things, a long magazine article about ["Why Americans Won't Do Dirty Jobs"](http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/why-americans-wont-do-dirty-jobs-11092011.html). What we actually learn from the article, however, is why American citizens won't put up with the kind of working conditions that immigrants without legal protection have no choice but to accept.* And once again, the real story is saved for the final paragraph. There, we meet Michael Maldonado, a young immigrant who has remained in Alabama and gets up at 4:30 to work at a fish processor. "With the business in desperate need of every available hand, it's not a bad time to test just how much the bosses value his labor", the article observes. Maldonado himself is well aware of his increased leverage. "If you pay me a little more---just a little more---I will

stay working here,” is how he puts it. "Otherwise, I will leave. I will go to work in another state."

(\* *Lest I be misconstrued: this does not mean that I think the Alabama law was a good idea. All this story shows is that driving away immigrants can, in fact, create a situation of labor scarcity. Unlike [Walter Benn Michaels](http://jacobinmag.com/blog/2011/08/tea-party-patriots-against-neoliberalism/), I don't think that's enough to recommend an anti-immigrant politics. I still think the policy is immoral and inconsistent with a principle of internationalism, because its effects on the labor market come at the expense of Latin American workers who are generally even poorer than their American counterparts.*)

All of this is amusing, but it also raises a dilemma for those of us who would like to use labor scarcity as a cudgel to drive high wages and labor-saving innovation, and thereby [harness the drive for relative surplus value](http://www.peterfrase.com/2012/02/a-victory-at-foxconn/) in the service of increasing productivity and decreasing the burden of work. In order for the increased bargaining power of labor to have its desired effects, capitalists must actually behave the way their economic ideology claims they should---that is, they must respond to incentives, rather than whining about having to pay their workers and demanding that the state guarantee their cheap labor supply.

But it turns out that nobody hates a free market more than the capitalist class. It was Adam Smith who [observed that](http://geolib.com/smith.adam/won1-10.html) "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices." The unwillingness of really existing capitalism to face market competition goes beyond a complacent assumption of the right to cheap labor. It's at the foundation of Ashwin Parameswaran's [far-reaching account](http://www.macroresilience.com/2011/12/07/the-great-recession-business-investment-and-crony-capitalism/) of our current troubles, which he traces to a "system where incumbent corporates do not face competitive pressure to engage in risky exploratory investment."

This then leads to the troubling (for a radical) notion that the operation of capitalism is too important to be left to the capitalists, and so the workers' movement must do some of their work for them. This is one of the intriguing ideas that runs through the Italian "workerist" Marxist tradition, and it's something that always bemused me. For all that *operaismo* and its descendants have become a hip, ultra-left alternative to staid traditional Marxism in certain circles, one of the tradition's core claims is that the workers' movement is historically tasked with *rationalizing capitalism*, helping Capital to achieve its own destiny. Mario Tronti, in [*Workers and Capital*](http://www.reocities.com/cordobakaf/tronti_workers_capital.html), puts it like this:

> After a partial defeat even following a simple contractual battle, __capital is violently pushed to having to come to terms with itself__, i.e., to reconsider precisely the quality of its development, to repropose the problem of the relation with the class adversary not in a direct form, but mediated by a type of general initiative which involves __the reorganization of the productive process, the restructuring of the market, rationalization at the factory, and the planning of society.__

On this reading, a big part of the historical mission of the Left was to make capitalism as revolutionary in reality as it was in its own ideological self-conception. Marx wrote admiringly of the [revolutionary élan](http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm#007) of the bourgeoisie, which "cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society." But according to Tronti, the capitalist must be dragged kicking and screaming into this revolutionary fervor. Just as Corey Robin argues that right wing political theory [borrows from its revolutionary antagonists in its defense of hierarchy](http://coreyrobin.com/new-book/), capitalist production adopts radical measures to defend the prerogatives of accumulation, but only in response to working class challenges. Creative destruction is only ignited by the sparks thrown off from class struggle.

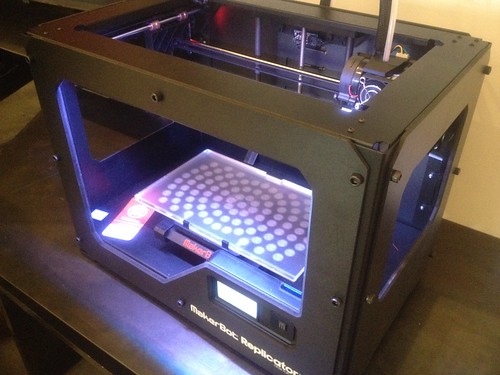

The idea that dynamism and innovation must be forced on capitalism from the outside recurs in a different way in David Graeber's essay for the [re-launched *Baffler*](http://thebaffler.com/) (not online, but the whole issue is worth buying). In a move reminiscent of both Parameswaran and [Tyler Cowen](http://www.amazon.com/The-Great-Stagnation-Low-Hanging-ebook/dp/B004H0M8QS), Graeber laments that we are living in an age of technological stagnation, in which "the projected explosion of technological growth everyone was expecting---the moon bases, the robot factories---fail[ed] to happen". The explanation he proposes is that the wellsprings of invention and creativity have been corporatized and bureaucratized, administered in a away that favors caution over breakthroughs. "[E]ven basic research", he argues, "now seems to be driven by political, administrative, and marketing imperatives that make it unlikely anything revolutionary will happen." Academia, meanwhile, has been transformed from "society's refuge

for the eccentric, brilliant, and impractical" into "the domain of professional self-marketers." Looking back at a bygone age of rapid progress, Graeber---like Tronti---sees a system that had to be forced into innovating by a hostile antagonist; in his account, however, it is the Soviet Union rather than the domestic labor movement that plays the starring role.

Graeber concludes by insisting that capitalism is neither "identical with the market" nor "inimical to bureaucracy". He implies that capitalism today finds itself where its Soviet twin was a few decades ago---a stagnant, bureaucratized order, incapable of reinvention or reform. He is ultimately a technological optimist---he is careful to distance himself from anti-industrial strains of anarchism---but he insists a break with capitalism must precede a return to technological dynamism:

> To of begin setting up domes on Mars, let alone to develop the means to figure out if there are alien civilizations to contact, we're going to have to figure out a different economic system. Must the new system take the form of some massive new bureaucracy? Why do we assume it must? Only by breaking up existing bureaucratic structures can we begin. And if we're going to invent robots that will do our laundry and tidy up the kitchen, then we're going to have to make sure that whatever replaces capitalism is based on a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth and power---one that no longer contains either the super-rich or the desperately poor willing to do their housework. Only then will technology begin to be marshaled toward human needs.

As a long-term vision, I agree with Graeber on this. The question is whether all of these issues can be left for after the revolution, or if there is a more reformist project we can engage with in the meantime. What does it mean if Graeber is right that capitalism tends toward bureaucratic inertia, and Parameswaran is right that our economy is held back by incumbents barring the way to creative destruction, and Tronti is right that it's the workers who ultimately force innovation on Capital? Maybe it means that until we can get rid of the capitalist class, we have to force them to bend to the forces of the market, rather than cling to their [patent monopolies](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/patents-are-not-free-trade-24567) and their God-given right to cheap labor.

Dean Baker argues, in [*The End of Loser Liberalism*](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/books/the-end-of-loser-liberalism), that progressives should reject the notion that they are in favor of regulation while the right is in favor of free markets. He insists that, understood correctly, everything from the defense of Medicare and Social Security to the [critique of "free" trade agreements](http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/manufacturing-jobs-still-matter-as-does-the-dollar) can be understood as part of the project of ensuring that "the logic of the market leads to progressive outcomes". It's easy to see this as a kind of rhetorical trick, but maybe it's just that capitalists can never be trusted to properly run a capitalist society. The great irony of Tronti's reading of capitalist development is that it's us anti-capitalist rebels who end up animating the logic of Capital in spite of ourselves---at least until we manage to break that logic altogether.

This perspective also casts the figure of [the left neoliberal](http://www.peterfrase.com/2012/03/the-rent-is-too-damn-high/) in a different light. The arguments I've described as left-neoliberal rely on certain free market tropes: competition, deregulation, efficiency. But taking such tropes seriously is perhaps more subversive than it appears, since actually existing neoliberal capitalism is not consistently based on any of these principles. It is instead, [as David Harvey has said](http://mrzine.monthlyreview.org/2006/lilley190606.html), a project of class power. In another of his essays, ["Against Kamikaze Capitalism"](http://shiftmag.co.uk/?p=389), Graeber contends that "Whenever there is a choice between the political goal of undercutting social movements---especially, by convincing everyone there is no viable alternative to the capitalist order---and actually running a viable capitalist order, neoliberalism means always choosing the first." So perhaps it's not so surprising to see University of Chicago finance professors attempting to [save capitalism from the capitalists](http://www.amazon.com/Saving-Capitalism-Capitalists-Unleashing-Opportunity/dp/0609610708), while two other mainstream economists express their hope that it will be Occupy

Wall Street that ultimately helps [save capitalism from itself](http://www.huffingtonpost.com/daron-acemoglu/us-inequality_b_1338118.html).