April 1 is "Census Day", the day on which you're supposed to have turned in your response to the 2010 census. Of course, lots of people haven't returned their form, and the Census Bureau even has a map where you can see how the response rates look in different parts of the country.

Lately, there's been a lot of talk about the possibility that conservatives are refusing to fill out the census as a form of protest. This behavior has been encouraged by the anti-census rhetoric of elected officials such as Representatives Michelle Bachman (R-MN) and Ron Paul (R-TX). In March, the Houston Chronicle website reported that response rates in Texas were down, especially in some highly Republican areas. And conservative Republican Patrick McHenry (R-NC) was so concerned about this possible refusal--which could lead conservative areas to lose federal funding and even congressional representatives--that he went on the right-wing site redstate.com to encourage conservatives to fill out the census.

Thus far, though, we've only heard anecdotal evidence that right-wing census refusal is a real phenomenon. Below I try to apply more data to the question.

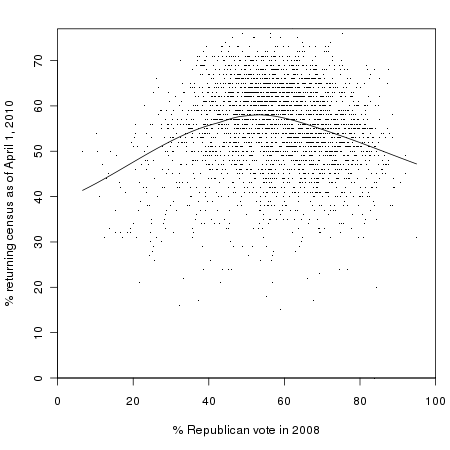

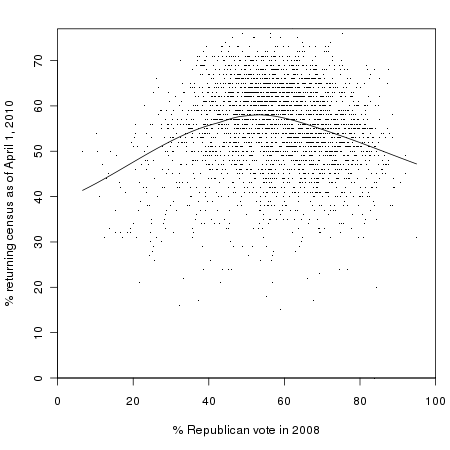

The Census Bureau provides response rates by county in a downloadable file on their website. The data in this post were downloaded on April 1. To get an idea of how conservative a county is, we can use the results of the 2008 Presidential election, and specifically Republican share of the two-party vote--that is, the percentage of people in a county who voted for John McCain, with third-party votes excluded. The results look like this:

It certainly doesn't look like there's any overall trend toward lower participation in highly Republican counties, and indeed the correlation between these two variables is only -0.01. In fact, the highest participation seems to be in counties that are neither highly Democratic nor highly Republican, as shown by the trend line.

So, myth: busted? Not quite. There are some other factors that we should take into account that might hide a pattern of conservative census resistance. Most importantly, many demographic groups that tend to lean Democratic, such as the poor and non-whites, are also less likely to respond to the census. So even if hostility to government were holding down Republican response rates, they still might not appear to be lower than Democratic response rates overall.

Fortunately, the Census Bureau has a measure of how likely people in a given area are to be non-respondents to the census, which they call the "Hard to Count score". This combines information on multiple demographic factors including income, English proficiency, housing status, education, and other factors that may make people hard to contact. My colleagues Steve Romalewski and Dave Burgoon have designed an excellent mapping tool that shows the distribution of these hard-to-count areas around the county, and produced a report on the early trends in census response around the country.

We can test the conservative census resistance hypothesis using a regression model that predicts 2010 census response in a county using the 2008 McCain vote share, the county Hard to Count score, and the response rate to the 2000 census. Including the 2000 rate will help us further isolate any Republican backlash to the census, since it's a phenomenon that has supposedly arisen only within the last few years. Since different counties can have wildly differing population densities, the data is weighted according to population.* The resulting model explains about 70% of the variation in census response across counties, and the equation for predicting the response looks like this:

The coefficient of 0.06 for the Republican vote share variable means that when we control for the 2000 response rate and the county HTC score, Republican areas actually have higher response rates, although the effect is pretty small. If two counties have identical HTC scores and 2000 response rates but one of them had a 10% higher McCain vote in 2008, we would expect the more Republican county to have a 0.6% higher census 2010 response rate. **

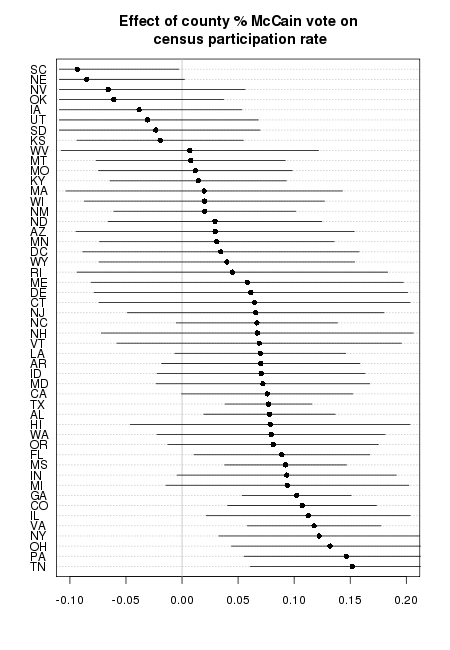

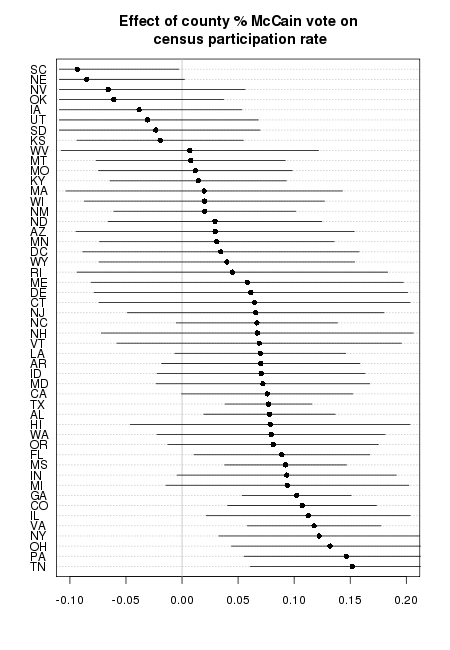

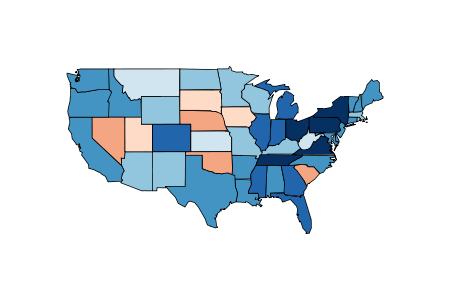

Now, recall that the original news article that started this discussion was about Texas. Maybe Texas is different? We can test that by fitting a multi-level model in which we allow the effect of Republican vote share on census response to vary between states. The result is that rather than a single coefficient for the Republican vote share (the 0.06 in the model above), we get 50 different coefficients:

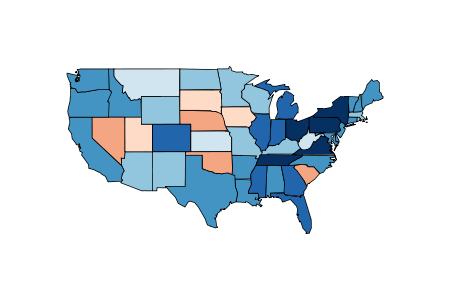

Or, if you prefer to see your inferences in map form:

The reddish states are places where having more Republicans in a county is associated with a lower response rate to the census, and blue states are places where more Republican counties are associated with higher response rates.

We see that there are a few states where Republicans seem to have lower response rates than Democratic ones, such as South Carolina and Nebraska. Even here, though, the confidence intervals are crossing zero or close to it. And Texas doesn't look particularly special, the more Republican areas there seem to have better response rates (when controlling for the other variables), just like most other places.

So given all that, how can we explain the accounts of low response rates in Republican areas? The original Houston Chronicle news article says that:

In Texas, some of the counties with the lowest census return rates are among the state's most Republican, including Briscoe County in the Panhandle, 8 percent; King County, near Lubbock, 5 percent; Culberson County, near El Paso, 11 percent; and Newton County, in deep East Texas, 18 percent.

OK, so let's look at those counties in particular. Here's a comparison of the response rate to the 2000 census, the response this year, and the response that would be predicted by the model above. (These response rates are higher than the ones quoted in the article, because they are measured at a later date.)

|

Population |

Response,

2000 |

Response,

2010 |

Predicted

Response |

Error |

Republican

vote, 2008 |

| King County, TX |

287 |

48% |

31% |

43% |

12% |

95% |

| Briscoe County, TX |

1598 |

61% |

41% |

51% |

10% |

75% |

| Culberson County, TX |

2525 |

|

38% |

|

|

34% |

| Newton County, TX |

14090 |

51% |

34% |

43% |

9% |

66% |

The first thing I notice is that the Chronicle was fudging a bit when it called these "among the state's most Republican" counties. Culberson county doesn't look very Republican at all! The others, however, fit the bill. And for all three, the model does substantially over-predict census response. (Culberson county has no data for the 2000 response rate, so we can't get a prediction there.) What's going on here? It looks like maybe there's something going on in these counties that our model didn't capture.

To understand what's going on, let's take a look at the ten counties where the model made the biggest over-predictions of census response:

|

Population |

Response,

2000 |

Response,

2010 |

Predicted

Response |

Error |

Republican

vote, 2008 |

| Duchesne County, UT |

15701 |

41% |

0% |

39% |

39% |

84% |

| Forest County, PA |

6506 |

68% |

21% |

57% |

36% |

57% |

| Alpine County, CA |

1180 |

67% |

17% |

49% |

32% |

37% |

| Catron County, NM |

3476 |

47% |

17% |

39% |

22% |

68% |

| St. Bernard Parish, LA |

15514 |

68% |

37% |

56% |

19% |

73% |

| Sullivan County, PA |

6277 |

63% |

35% |

53% |

18% |

60% |

| Lake of the Woods County, MN |

4327 |

46% |

27% |

45% |

18% |

57% |

| Cape May County, NJ |

97724 |

65% |

36% |

54% |

18% |

54% |

| Edwards County, TX |

1935 |

45% |

22% |

39% |

17% |

66% |

| La Salle County, TX |

5969 |

57% |

26% |

43% |

17% |

40%% |

I have a hard time believing that the response rate in Duchesne county, Utah is really 0%, so that's probably some kind of error. But as for the rest, most of these counties are heavily Republican too, which suggests that maybe there is some phenomenon going on here that we just aren't capturing. But now look at the counties where the model made the biggest under-prediction--where it thought response rates would be much lower than they actually were:

|

Population |

Response,

2000 |

Response,

2010 |

Predicted

Response |

Error |

Republican

vote, 2008 |

| Oscoda County, MI |

9140 |

37% |

66% |

36% |

-30% |

55% |

| Nye County, NV |

42693 |

13% |

47% |

22% |

-25% |

57% |

| Baylor County, TX |

3805 |

51% |

66% |

45% |

-21% |

78% |

| Clare County, MI |

31307 |

47% |

62% |

42% |

-20% |

48% |

| Edmonson County, KY |

12054 |

55% |

65% |

46% |

-19% |

68% |

| Hart County, KY |

18547 |

62% |

68% |

49% |

-19% |

66% |

| Dare County, NC |

33935 |

35% |

57% |

39% |

-18% |

55% |

| Lewis County, KY |

14012 |

61% |

66% |

48% |

-18% |

68% |

| Gilmer County, WV |

6965 |

59% |

63% |

45% |

-18% |

59% |

| Crawford County, IN |

11137 |

62% |

68% |

51% |

-17% |

51% |

Most of these are Republican areas too!

So what's going on? It's hard to say, but my best guess is that part of it has to do with the fact that most of these are fairly low-population counties. With a smaller population, these places are going to show more random variability in their average response rates than the really big counties. Smaller counties tend to be rural counties, and rural areas tend to be more conservative. Thus, it's not surprising that the places with the most surprising shortfalls in census response are heavily Republican--and that the places with the most surprising high response rates are heavily Republican too.

At this point, I have to conclude that there really isn't any firm evidence of Republican census resistance. That's not to say it doesn't exist. I'm sure it does, even if it's not on a large enough scale to be noticeable in the statistics. It's also possible that the Republican voting variable I used isn't precise enough--the sort of people who are most receptive to anti-census arguments are probably a particular slice of far-right Republican. And it's always difficult to make any firm conclusions about the behavior of individuals based on aggregates like county-level averages, without slipping into the ecological fallacy. Nonetheless, these results do suggest the strong possibility that the media have been led astray by a plausible narrative and a few cherry-picked pieces of data.

* Using unweighted models doesn't change the main conclusions, although it does bring some of the Republican vote share coefficients closer to zero--meaning that it's harder to conclude that there is any relationship between Republican voting and census response, either positive or negative.

** All of these coefficients are statistically significant at a 95% confidence level.