The limits of anti-Trumpism

July 6th, 2020 | Published in Politics, Socialism, xkcd.com/386

Max Elbaum is a friend and sometime political mentor. He's also the author of Revolution in the Air, the definitive history of the "New Communist Movement" within the New Left, a tendency that has been broadly influential on my politics as well. So I always pay close attention to his comments on left strategy.

In a recent article for Organizing Upgrade, Max lays out his view of the current terrain for socialists. And while there's much there to agree with, the clear and unambiguous way that he makes his case shows some clear limits to the kind of popular front he wants to exhort socialists to join.

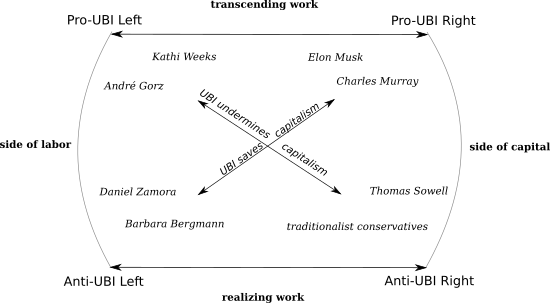

In Max's view, the Left after the end of the Bernie Sanders Presidential campaign is divided into two camps. One, the "Never Biden" camp, views the central dividing line in American politics in 2020 as being between workers and neo-liberal capitalists. This means that the enemy is not just Trump and the Republican party, but much of the Democratic establishment as well. Within my organization, the Democratic Socialists of America, Max identifies this analysis with the so-called "Bernie or Bust" resolution adopted at our 2019 convention, which bars DSA from endorsing any non-Bernie candidate for President in 2020.

Max goes on to reject this analysis in favor of one which sees American politics as being defined by the popular front against Trumpism:

Today’s which-side-are-you-on dividing line is between a racist authoritarian bloc led by Donald Trump vs. a larger but much more heterogeneous array of forces that, from different angles, regard Trumpism as a dire threat to their rights and interests.

Both the Trump and anti-Trump camps are multi-class alliances. Both contain advocates of neoliberal economics. The conflict between them is nonetheless quite sharp. The dividing line is the system of white supremacy. This racist material relation is not an “add-on” that piles oppression on top of exploitation for certain groups of workers. Rather, it is integral to and interwoven with relations of exploitation in ways that have decisively shaped political conflict in the U.S. since its origins in 1619.

Max goes on to persuasively argue that segments of the ruling class have self-interested reasons to oppose the Trump regime, both because they are personally threatened by its authoritarianism, and because they see it as opposed to the true long-term interests of the U.S. ruling class. But his payoff, and the point that is bound to me most controversial, is what he thinks this implies for socialist strategy.

The long and short of it is that socialists are exhorted that we must above all prioritize "throwing ourselves into the anti-Trump coalition is the best route for both ousting Trump and building the strength of progressive movements and the socialist left."

The problem is not that the analysis is entirely wrong, but that it divides the political options in such a way that important features of the present moment are left out. In his closing, Max presents the possible slogans as being either "Beat Trump" or "Never Biden". That is, socialists must choose either to direct all their energy to electing Biden, or dismiss the significance of this fight on the grounds that Biden is too reactionary and compromised to be worth fighting for. The former, he suggests, is the path toward building strength, the latter towards political marginality and isolation from rising multi-racial progressive coalitions.

This would be a more persuasive argument if---as, from reading Max's text, sometimes appears to be the case---the sum total of what is happening in U.S. politics at the moment were defined by the Presidential election. But the concrete organizing situation is more complex like this, as we can see by considering something that Max refers to repeatedly but never analyzes in detail: the Black Lives Matter uprisings in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

From the way these uprisings are discussed in the article, you would think that they were protests against the Trump regime and the Republican Party. It is certainly true that the police themselves---both rank and file and leadership---are part of Trump's base. So too, the "blue lives matter" counter-organizing overlaps substantially with the hardest core of Trump's support.

But the elected leadership that the protests have targeted most directly are mayors and city councils that are largely Democrats. The call to defund the police, which has arisen as the most exciting and distinctive demand of the current wave of struggles, is directed at municipal governments like those of Minneapolis and New York, where police departments have only become more brutal and taken up more of the municipal budget under decades of supposedly liberal leadership.

Mayors like Jacob Frey of Minneapolis and Bill de Blasio have found themselves at odds with movements in the street and on the side of the police. And yet, according to Max's analysis, these politicians are part of the very anti-Trump front we are being asked to join!

This might be possible, and even desirable, if the only issue in play were the Presidential election. (Although Biden himself has made this difficult by being very clear in his pro-police stance.) But defunding the police is an issue now, as budgets are being written and passed in a context of pandemic-driven austerity.

A similar argument can be made about the other major driver of politics at the moment, the COVID-19 pandemic. It is true that Trump's total failure to deal with the pandemic, and his attempt to politicize epidemiology and promote conspiracy theories instead, has created a powerful basis for opposing him and the forces he represents.

And yet once again, it has been not just Republicans but also neoliberal Democrats, who Max wants us to see a sallies against Trump, who have been the ones botching the response and using the coronavirus as a pretext for their pre-existing pro-capitalist agenda. In New York, it was Governor Andrew Cuomo---whose media strategy for a time made him a liberal darling in contrast to Trump---who forced through cuts to Medicaid in the middle of a pandemic in a way that managed to provoke even the reliably pro-business Senator Chuck Schumer to rebuke him from the left. And in Philadelphia, mayor Jim Kenney responded to call to defund the police by proposing a budget that increased police funding while cutting social services.

These are only two examples relatively close to where I'm located, but there are others around the country. The point is that it's easy to make politics all about the anti-Republican popular front when you abstract away from the context and the content of the protest movements and organizing that are actually going on.

My intention in arguing all of this is not to uphold the "Never Biden" pole of the argument, which, as Max constructs it, is not particularly appealing. But this is because the argument is laid out in a way that presumes that we all organize in a context where the only choice is to be all in for Biden, or to be politically irrelevant until November. And this, as the foregoing suggests, is manifestly not the case.

As a final example, I'll use my local organizing context in New York's Hudson Valley, a couple of hours north of New York City. Like much of the rest of the country, we've seen waves of unprecedented mobilization in the past weeks, with crowds of hundreds or thousands gathering in the small towns and cities that dot our region. And the call to defund the police has been raised into consciousness and put before local elected officials in unprecedented ways.

Our region is divided between de-industrialized, mostly non-white cities and more affluent and white exurban and rural areas. The threat of the Right is very real here, in both its generically pro-Trump and overtly Nazi forms. But the Biden-Trump contest itself lingers more in the background, even as we pursue police defunding campaigns in cities largely run by Democrats.

The reason for this is fairly obvious: New York State will almost certainly vote for Biden, due to the power of New York City's vote. Where electoral politics in my region has been contested lately, it has once again been a matter not of anti-Trump popular frontism but rather, the left-versus-neoliberals fight that Max's analysis seeks to strategically sideline. Jamaal Bowman won his primary over Eliot Engel, a fairly conventional Democrat (if especially hawkish on foreign policy), in a contest that pitted progressive forces against everyone from Nancy Pelosi to Hillary Clinton to Republican Super PACs.

Virtually nobody on the left disagrees with the proposition that defeating Donald Trump is important and necessary. And in some places and some political contexts, prioritizing Presidential-level electoral organizing will make the most sense. But the reality for many of us is that the fight against capital's liberal face and its conservative one are both happening right now, and it doesn't make sense, as either principle or strategy, to put one of these struggles on the shelf until after November.